|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 17 , Issue 102015Weekly eZine: (371 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

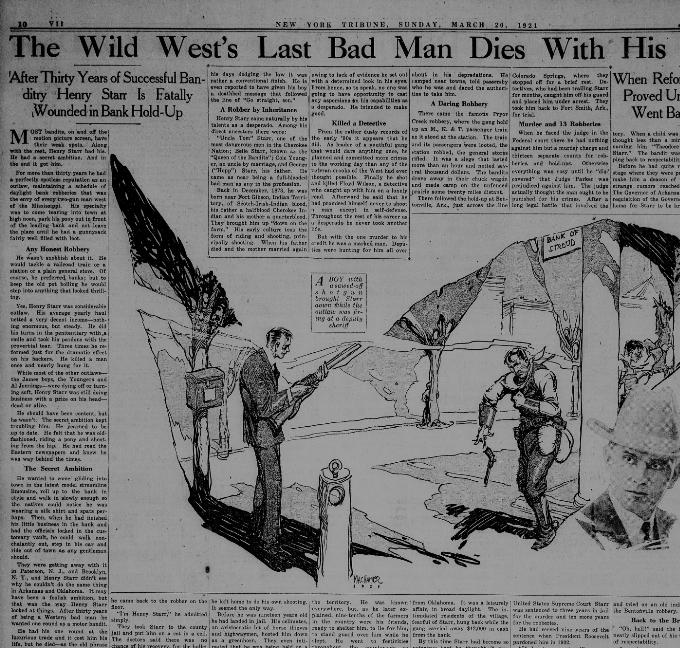

Wild West's Last Badman Dies March 1921

It was in the New York Tribune, Sunday, 20 March 1921, page 76, that we learned of "The Wild West's last Bad man Dies With Boots On. After thirty years of successful Banditry Henry Starr was fatally wounded in a bank hold-up.

Most bandits, on and off the motion picture screen, have their weak spots. Along with the rest, Henry Starr had his. He had a secret ambition. And in themed it got him.

For more than thirty years he had a perfectly spotless reputation as an outlaw, maintaining a schedule of daylight bank robberies that were the envy of every two-gun man west of the Mississippi. His specialty was to come tearing into town at high noon, park his pony out in front of the leading bank and not leave the place until had a gunlock fairly we'll filled with loot.

Starr wasn't snobbish about it. He would tackle a railroad train or a station or a plain general store. Of course, he preferred banks; but to keep the old pot boiling he would step into anything that looked thrilling.

Henry Starr was considerable outlaw. His average yearly haul netted a very decent income, nothing enormous, but steady. He did his turns in the penitentiary with a smile and took his pardons with the proverbial tear. Three times he reformed just for the dramatic effect on his backers. He killed a man once and nearly hung for it.

While most of the other outlaws, the James boys, the Youngers and Al Jennings, were dying off or turning soft, Henry Starr was still doing business with a price on his head. Dead or Alive.

Starr should have been content, but he wasn't. The secret ambition kept troubling him. He yearned to be up to date. He fell that he was old-fashioned, riding a pony and shooting from he hip. He had read the Eastern newspapers and knew he was way behind the times.

The Secret Ambition

Starr wanted to come gliding into town in the late model streamline limousine, roll up to the bank in style and walk in slowly enough so the natives could notice he was wearing a silk

shirt and spats perhaps. Then, when he had finished his little business in the bank and had the officials locked in the customary vault, he would walk nonchalantly out, step in his car and ride out of town as any gentleman should.

They were getting away with it in Paterson, N.J., and Brooklyn, N.Y., and Starr didn't wee why he couldn't do the same thing in Arkansas and Oklahoma. It may have been a foolish ambition, but that was the way Henry Starr looked at things. After thirty years of being a Western bad man he wanted one round as a motor bandit.

He had his one round at the luxurious trade and it cost him his life, but he died, as the old phrase has it, with his boots on, and he died happy. For a few hours he had been a motor bandit.

Less than month ago, into the sleepy little Ozark town of Harrison, Arkansas, there rattled a mud-be-spattered little flivver. Besides the driver there were three men, all wearing masks and armed to the teeth. If any one saw the same sight here in the East he would turn to look for the camera man following in the next car. But there wasn't any camera man in this case.

The car drew up to the curb in front of the People's National Bank of Harrison. Three men hopped out and sauntered into the bank. The driver stayed at the wheel, the motor throbbing violently as though it were easier to be off again.

Inside the bank the three masked men had complete charge of the situation. With six guns waving in the air,there was no offer of resistance. The few startled customers were backed against the wall, the bank officials crowded around the door of the big vault.

"Get back there!" yelled the leading bandit, and the crowd obeyed.

Cringing way in the back part of the vault, W. J. Meyers, a former president of the bank, felt something hard sticking into his back. He turned and saw an old rifle that he had left there ten years before, providing for just such an emergency.

Cautiously he crept toward the doorway of the vault. He thought the gun was loaded, but he couldn't be sure.

One of the robbers was leaning over a cash drawer directly opposite the vault. Meyers shoved the muzzle of the rifle against his side and fired. The robber crumpled in a miserable heap at his feet.

"Don't shoot again!" he gasped.

The other robbers took to their heels. Meyers fired a single wild shot after the speeding flivver as it scurried down the main street. Then he came back to the robber on the floor.

"I'm Henry Starr," he admitted simply.

They took Starr to the county jail and put him on a cot in a cell. The doctors said there was no chance of his recovery, for the bullet had severed his spinal cord. He lingered between life and death for four days, conscious all the time. His wife came from Tulsa and his son from Muskogee, where he was attending school.

For a man who had spent most of his days dodging the law it was rather a conventional finish. He was even reported to have given his boy a deathbed message that followed the line of "Go straight, son."

Henry Starr came naturally by his talents as a desperado. Among his direct ancestors there were:

"Uncle Tom" Starr, one of the most dangerous men in the Cherokee Nation; Belle Starr, known as the "Queen of the Bandits;" Cole Younger, an uncle by marriage, and George "Hopp" Starr, his father. He came as near being a full-blooded bad man as any in the profession.

Back in December, 1873, he was born near Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, of Scotch-Irish-Indian blood, his father a halfblooded Cherokee Indian and his mother a quarter blood. They brought him up "down on the farm." His early culture took the form of riding and shooting, principally shooting. When his father died and the mother married again he left home to do his own shooting. It seemed the only way.

Before he was nineteen years old Henry Starr had landed in jail. His cellmates, an aristocratic lot of horse thieves and highwaymen, hooted him down as a greenhorn. They even intimated that he was being held on a false charge. It was bitter persecution for a young man trying to get along. But he put up a brave front. He thrashed the sheriff in a fist fight and defied the jailbirds who gathered around to taunt him.

When Henry was released next day owing to lack of evidence he set out with a determined look in his eyes. From hence, so to speak, no one was going to have opportunity to cast any aspersions on his capabilities as a desperado. He intended to make good.

From the rather dusty records of the early '90s it appears that he did. As leader of a youthful gang that would dare anything once, he planned and committed more crimes to the working day than any of the veteran crooks of the West had ever thought possible. Finally he shot and killed Floyd Wilson, a detective who caught up with him on a lonely road. Afterward he said that he had promised himself never to shoot a man except in self-defense. Throughout the rest of his career as a desperado he never took another life.

But with the one murder to his credit he was marked man. Deputies were hunting for him all over the territory. He was known everywhere, but, as he later explained, nine-tenths of the farmers in the country were his friends, ready to shelter him, to lie for him, to stand guard over him while he slept. He went to festivities throughout the countryside, to dances, where volunteers maintained a guard at the door on the lookout for the deputies.

To show his contempt for the United States marshals hunting for hi, Starr fitted out a check and ammunition wagon and rove openly about in his depredations. He camped near towns, told passersby who he was and dared the authorities to take him.

There came the famous Pryor Creek robbery, where the gang held up an M. K. & T. passenger train as it stood at the station. The train and its passengers were looted, the station robbed, the general stores rifled. It was a siege that lasted more than an hour and netted several thousand dollars. The bandits drove away in their chuck wagon and made camp on the unfenced prairie some twenty miles distant.

There followed the hold-up at Bentonville, Arkansas, jut across the line from Oklahoma. It was a leisurely affair, in broad daylight. The intimidated residents of the village, fearful of Starr, hung back while the gang carried away $12,000 in cash from the bank.

By this time Starr had become so notorious that he thought it was time to leave the country. He said good-by to his gang and drove overland to Emporia, Kansas, with his sweetheart, whom he planned to marry. They intended to make their ultimate home in Mexico. Bad luck overtook the couple at Colorado Springs, where they stopped off for a brief rest. Detectives, who had been trailing Starr for months, caught him off his guard and placed him under arrest. They took him back to Fort Smith, Arkansas for trial.

When he faced the judge in the Federal court there he had nothing against him but a murder charge and thirteen separate counts for robberies and hold-ups. Otherwise everything was rosy until he "discovered" that Judge Parker was prejudiced against him. The judge actually thought the man ought to be punished for his crimes. After a long legal battle that involved the United states Supreme Court, Starr was sentenced to three years in jail for the murder and ten more years for the robberies.

Starr had served nine years of the sentence when president Roosevelt pardoned him in 1902.

"If I let you out will you go straight?" Roosevelt asked him.

"Sure," said Starr, and the first "reformation" was under way.

A year later he married Miss Ollie F. Griffin, part Cherokee, a girl of considerable culture, who had been teaching in the schools of the territory. When child was born Starr thought less than a minute before naming him "Theodore Roosevelt Starr." The bandit was fast slipping back to respectability.

Before he had quite reached the stage where they were preparing to make him a deacon of the church strange rumors reached his ears. The Governor of Arkansas had made requisition of the Governor of Oklahoma for Starr to be brought over and

tried on an old indictment for the Bentonville robbery.

Several years of tremendous activity followed. With a newly organized gang of desperadoes Starr branched out and included many new states in his area of operations. He would spend a few months in Colorado, then hop to Kansas, shoot over to Missouri and back to the old familiar territory in Oklahoma Arkansas.

Finally pursuit became so warm that he and a pal called "Stumpy" set out for New Mexico, blazing a trail of hold-ups as they went. Through the treachery of a close friend they were caught at a mining camp in Arizona near the Mexican border in May, 1909, and returned to Colorado.

In November of the same year Starr was sentenced to from seven to twenty-five years in the Canyon City penitentiary. Thomas J. Tynan, one of the first prison officials to believe firmly in the honor system, made Starr one of his honor squad. From long experience Starr's prison behavior was perfect. After serving less than five years of his sentence he was breathing the fresh air again and organizing a new gang to raise havoc in the wild Southwest.

Shortly after his Starr conceived and executed the most sensational feat of his career, the famous Stroud bank robbery.

With two other men he walked quietly into the Stroud National Bank at Stroud, Oklahoma, and called "Hands Up!" Just a block down the street four other members of the gang were invading the Frist national Bank with the same command.

Dangling in the front door of the Stroud National Bank was a big placard, signed by the Governor of Oklahoma, reading: "$1,000 Reward for Henry Starr - Dead or alive!"

Starr never flicked an eye at the warning. Instead, he marched straight in and corralled the officials, J. H. Charles, president, and Lee Patrick, vice-president, in the back.

Flinging out a flour sack, he said, Empty the safe and put it in that."

At about this stage of the game there came an echo of shots from down the street. Soon the shooting became general. News of the hold-up spread throughout the town. Starr joined his own smoke to the main barrage.

Paul Curry, a mere boy but a close follower of the adventures of Nick After, ran through the streets looking for a weapon to attack the bandits. At a meat market he found a murderous, short-barreled rifle that carried a big, snub-nosed lead bullet. The local butcher used it to kill his hogs.

Starr could have shot the boy as he came toward him, but he had a good target further down the street in one of his old enemies, a deputy sheriff. The boy fired and Starr fell heavily, a bullet in his hip. Louis Estes, Starr's chief lieutenant and leader of the attack on the other bank, also dropped with a bullet inches hip. The other bandits took alarm and got away.

In a doctor's office over the bank Starr had robbed, Starr was laid out on the table.

"Sure, I'm Henry Starr," he said. "What did the kid shoot me with?"

When they told him he grumbled. "A hog gun, eh? And a kid, too. I wouldn't have minded it if had been a man and a regular gun meant for humans."

For this robbery Starr was sentenced to another twenty-five years in the Oklahoma penitentiary. Four years later he was out again, paroled by Governor Robinson for more good behavior.

Into the Movies

This necessitated his going to all the bother of reforming once more. As his wife had died, he remarried in February, 1920, making his new home around Tulsa. It grew rather tame, just being a plain citizen, so he thought up a new device for getting a thrill out of life. He planned to put himself in the movies, with a scenario sketched form real life. He traveled around with his film, giving a lecture the same night it was shown and billing himself as the "original bad man of America."

But there was neither the financial success nor the thrill to this business that he had anticipated. A new generation had grown up, not so interested in the two-gun man of the old day as in the modern motorized, silk-shirted bandit. Realizing this was somewhat of a shock to Henry Starr.

No man likes to feel that the times had outstripped him, Henry Starr least of all. He decided to try his hand at the new game. It proved a fatal mistake.

As has already been mentioned, and as his old cronies out to the Western towns insist on repeating, Henry Starr died with his boots on.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments)

| Receive

updates ( subscribers) |

Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |