|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 15 , Issue 112013Weekly eZine: (371 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

History of Rockbridge County, Virginia - Robert E. Lee

This week we bring you some history of Robert E. Lee as president of Washington College, in Lexington, Rockbridge county, Virginia. We will also look at his father, Henry Lee, whose own father was a first cousin to Richard Henry Lee, a celebrated statesman of the Revolutionary period.

Henry Lee

Henry Lee was a graduate of Princeton College, and intended to enter the legal profession, but with the war for Independence breaking out before he had reached his majority, he became an officer in Washington's army. When he was 22 years of age, he was put at the head of a band that became famous as "Lee's Legion." It was his exploits on the present site of Jersey City, where Henry took 160 prisoners with the loss of scarcely a man, and given a gold medal.

At the close of 1780, at the rank of Lieutenant-colonel, when the American cause looked dark, he led his legion, 300 strong and composed of both cavalry and infantry, to join General Greene in the South. During the campaign of 1781 his services were invaluable. In 1791 he was chosen governor of his state, and a county was named for him. In 1794 he was commander of the army of 15,000 that was sent to put down the Whiskey Insurrection. Four years later, when war with France seemed imminent, he was advanced to the rank of major-general. While serving in Congress, he delivered the address on Washington that contains the well known phrase, "First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen." During the war of 1812 he was severely injured in Baltimore while defending an editor friend from a mob. From this hurt there was no full recovery. In the hope of benefit he visited the West Indies, but growing worse, he asked to be put ashore at cumberland Island, Georgia, so that he might die at the home of his late commander-in-chief. He was hospitably received by the widow of General Greene, and ended his days in her house, three weeks later, at the age of 62, 25 March 1818. Pursuant to an Act of the General assembly, the remains were removed to Lexington in 1913 to rest by the side of those of his still more distinguished son.

General Robert Edward Lee

Robert E. Lee was six feet tall, faultless in figure and unusually handsome in feature. His coal-black hair became very grey during the progress of the war. Until his second campaign he wore no beard except a mustache, but afterward his face was unshaven. An aged resident of Rockbridge county spoke of his countenance as noble and benignant and not suggestive of the warrior. But Lee was known to have a temper, as shown in the case of the dispatch that was dropped in a street of frederick and fell into the hands of McClellan. Lee avoided all display and ostentation, and set before young men an example of simple habits, manners, needs, words and duties. He wrote his daughters that "gentility, as well as self-respect, requires moderation in dress and gayety."

General Lee was almost a neighbor to General Washington, and enjoyed his confidence and esteem. As an alumnus of Princeton he was brought into close acquaintance with the founders of Liberty Hall. When Washington was studying what to do with the canal stock donated him by the state of Virginia, Lee was instrumental in directing his attention to the struggling academy. Lee sent his fourth child, Henry Lee, Jr., to study at Lexington, and the son was one of the early graduates of Liberty Hall. He died in france in 1837 at the age of 50, well-informed and author of several books. But General Lee owned land in Rockbridge and spent some of his time there. Lee was a planter, the tidewater soil was growing poor, and the unsettled period lasting from the beginning of the Revolution to the close of the war of 1812 was not conductive to material posterity.

As many other men of his class, Lee was in debt, but it was alleged that he did not allow such a matter to engross his thoughts. One of the anecdotes along this line was the effect that a Rockbridge credit needed his money, became impatient, and went with a constable to the general's home in Arnold's Valley, Light-Horse Harry, by which name he was familiarly known, was at home, and the callers had a delightful social hour. They left without saying a word about the writ, and the creditor was indifferent as to whether he should get his pay or not. The general's attitude might be styled an instance of unconscious and unpremeditated diplomacy.

Robert Edward Lee was born at Stratford, his father's manor house in Westmoreland county, the date of his birth being 19 January 1807. He was the youngest of the sons of Light-Horse Harry, and his mother was a second wife. he passed through West Point without a demerit, graduating in 1829 at the head of his class. His first service was in the Engineer Corps of the army of the United States. He entered the war with Mexico as a captain, and won such distinction under General Scott as to attain the rank of colonel at the close. In 1852-5, he was superintendent of West Point. He remained with the regular army until the spring of q86q, sending only portions of his time at Arlington, the estate near the city of Washington which was inherited by his wife, Mary Custis, a great-granddaughter of Martha Washington by her first husband. It was during a leave of absence that he was put in charge of the Federal troops sent to deal with John Brown at Harper's Ferry.

Opening Months of 1861

In the opening months of 1861 Lee was again at home at Arlington. He was now 54 years of age and in the full maturity of his powers. General Scott loved him as a son, and not only had the highest opinion of his military skill, but predicted that Lee would greatly distinguish himself if circumstances should ever place him at the head of an army. It was because of this reputation that he was offered the command of the field army that was to invade the South. Lee was very much opposed to secession. As to slavery, he said that if he were to own all the slaves in the United States he would set them free as a means of preserving the Union.

The political storm that was breaking caused him great distress of mind. A Union that could not be vindicated except by an appeal to force was repugnant to him as it was to all others nurtured in the same school of political thought. He believed that when the Lincoln administration adopted a coercive policy, the Union of 1788 was virtually dissolved, and that each of the competent states was at liberty to shift for itself. Lee, looking at the situation in this light, conceived that his first duty was to serve his native state, which from 1775 to 1788 had enjoyed a career practically independent. He therefore resigned his commission in the army. That he was entirely conscientious in this step was conceded by all students of American history. He decided his problem for himself and without attempting to influence even his sons.

Going to Richmond, Lee was made a major-general of the Virginia troops. The last day of August Lee was advanced to the rank of full general in the confederate service. In September he was in command on the Greenbrier. His operations in this quarter were inconclusive and of short duration. the following winter he was in charge of the engineering details of the defense of the Atlantic coast, particularly in South Carolina. This work was well done that Charleston was not occupied by the Federals until flanked by Sherman's army in the closing months of the war. In the spring of 1862, Lee was called to Richmond to act as military advisor to the Confederate president. When General Joseph E. Johnston was wounded at Seven Pines, May 31st, Lee was appointed to succeed him. Lee was then in his element, and for almost three years he remained at the head of the army of Northern Virginia.

The story of that superb organization was almost the story of the war itself. It was the spearhead and most successful factor of the Southern resistance. The great battles of the Peninsula, Second Manassas, Sharpsburg, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness, Spottsylvania, Cold Harbor, the siege of petersburg, and the campaign of maneuver against Meade in 1863 were all fought under the immediate direction of Lee. Sharpsburg was a drawn battle, and Gettysburg a reverse, but neither of these actions took place on the soil of lee's native state. Worn down by relentless attrition and cut off from its supplies, the army of Northern Virginia gave up the struggle at Appomattox, April 9, 1865. A few more weeks and the Southern Confederacy ceased to exist.

General Lee's Home

Lee's home had been appropriated by the Federal authorities. The summer of 1865 found the great Confederate chieftain living quietly on a plantation in Powhatan county. He turned down all inducements to begin a career in Europe, believing it his duty to remain with his own people and share their fortunes. Lee would not listen to any overture which had no other primary object than the capitalizing of his name. Yet some mode of breadwinning was necessary.

It was in the third year of the war General Lee had a severe attack of Laryngitis, followed by a rheumatic periodical inflammation. For sometime he could not exercise on foot or ride fact without being inconvenienced by a pain in the chest or by difficult breathing. There was gradual improvement, although he continued to have occasional attacks of muscular rheumatism.

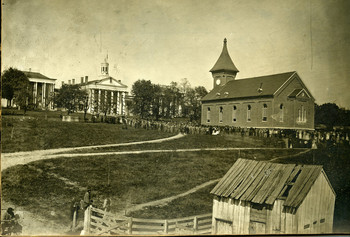

Washington College

It was at the meeting of trustees of Washington College, 4 August 1865, Bolivar Christian nominated General Lee as its president. Some say that when J. W. Brockenbrough was selected to carry the offer of the trustees to the general, he declined on the ground that neither he himself nor the college had any money for the traveling expenses that his clothes were not good enough. But the necessary money was raised and a friend loaned a new suit. Lee accepted the proffered office on the 24th of August 1865, stipulating that his duties were to be executive only, and that he was not to be asked to give classroom instruction. The following month he came to Lexington, riding his famous battle horse, Traveler, and was quietly inaugurated October 2, 1865.

During the five years that covered the final chapter of his life, General Lee was president of Washington College and a resident of Lexington. His salary was $1,500 and a cottage was built for himself and family.

The fortunes of the college were at this time at a low ebb. The building had been partially looted and the grounds were in disorder. The small endowment was unproductive, and the 50 students who presented themselves were wholly from Lexington and the country around. The magic of Lee's name, coupled with the affection in which he was held, would alone have swelled the student body to a goodly size and lent a great measure of success to his administration.

Robert E. Lee was not the man to treat his office as an easy, cushy job. A college presidency seemed a far remove from the leadership of a great army. yet it was in the educational field that Lee felt that he could be most useful to his people. Warfare had past and a period of transition had come to the South. The need of the time was constructive work, and this was more applicable to the young men of student age. Lee applied himself to his new sphere with diligence. Lee might have been a soldier of profession, but he was also a man of sound scholarship. He was everywhere, and his system of reports, instituted by himself and almost military in its exactness, caused his spirit and his influence to pervade every department. Lee kept himself informed of the progress and standing of every student. Lee was a firm president in administering reproof, yet gentle and fatherly. The attendance rapidly increased, and the school prospered and improvements were made in the college property. One of his earliest tasks was to build the chapel, in the basement of which was his office. This room was kept as nearly as possible in the same condition as when he last used it.

At Lexington Lee led a retired life, and did not mingle in society. Lee's pastime was to ride about the country. He once remarked that, "Traveler (his horse) was my only companion. He and I wander out into the mountains and enjoy sweet confidence." It was these expeditions that he did not go inside the farm homes, but as he was very fond of buttermilk he often called at them for a glass.

In the winter of 1869-70, his health began sensibly to fail, and in the spring he visited Georgia. There was some relief, but not for long. His final illness, which seized him as he was about to say grace at his dinner table, was a passive congestion of the brain resembling concussion, but without paralysis. After lying unconscious several days he died 12 October 1870.

The children of General Lee were seven. Three sons served in the confederate army, two of them attaining the rank of major-general.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments)

| Receive

updates ( subscribers) |

Unsubscribe

| © 2025. Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |