|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 14 , Issue 522012Weekly eZine: (374 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

History of Rockbridge County, Virginia - Establishing Rockbridge

In this week's of The OkieLegacy we continue with Oren F. Morton's book on The History of Rockbridge County, Virginia, with the establishing of Rockbridge county and the Cornstalk affair, Annals of 1778-1783).

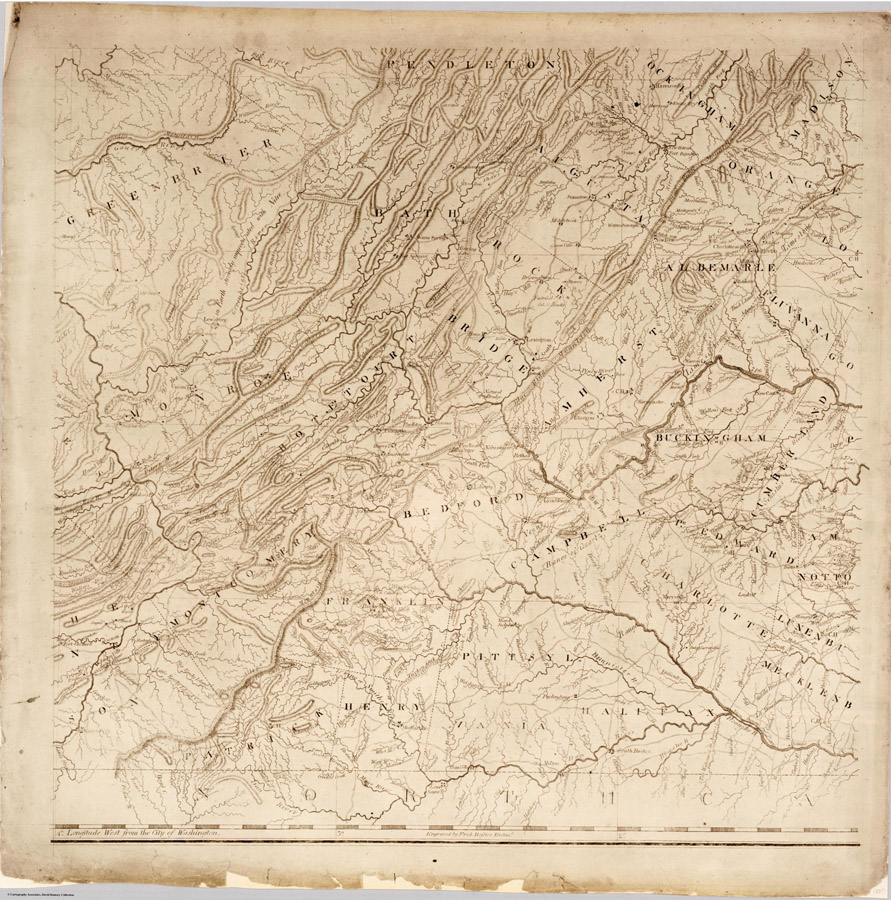

There was a house that John Lewis built near the site of Staunton in the summer of 1732 that was not within the recognized limits of any county. Until 1744 the blue Ridge was the treaty line between paleface and redskin. the first county organization to cross that barrier was Spottsylvania, which became effective in 1721. yet it came only to the South Fork of the Shenandoah, one extremity of the line touching the river in the vicinity of elk ton, the other about midway between Front royal and Bentonville. Orange was created in 1734, and organized in 1735. It was defined as extending westward to the uttermost limit claimed by Virginia. four years later, the portion of Orange west of the Blue Ridge was divided into the counties of Frederick and Augusta by a line running from the source of the Rapidan to the Fairfax Stone at the source of the North Branch of the Potomac. The present boundary between Rockingham and Shenandoah is a portion of this line.

During the westward march of population in Virginia, the practical area of a county had always been co-extensive with it s settled portion. The fact that Augusta once extended potentially to the Mississippi, did not mean that a juryman might have to travel hundreds of miles to attend court. When the first division of Augusta took place in 1769, probably not less than three-fourths of the inhabitants were living within a radius of fifty miles around Staunton. Of the other fourth, nearly all were within a few miles of a trail leading from Buchanan to Abingdon.

The first county to be set off from Augusta was Botetourt, which became effective January 31, 1770. The line separating it from the parent county was described in a report by James Trimble, the surveyor:

Beginning at two Chestnuts and a Black oak on the South Mountain by a Spring of pealed Creek on Amherst Line and running thence 55 degrees West 4 Miles 240 Poles to a Spanish Oak marked AC on the one Side and BC on the Other Side where the South River or Mary's Creek empties into the North Branch of James River, and up the North River to Kerr's Creek and up Kerr's Creek to the Fork of the said Creek at Gilmore's Gap. Then beginning at a chestnut and three Chestnut Oaks and a Pine at the upper Fork of Kerr's Creek and runneth the same Course to with North 55 degrees West, 23 and one half miles, Crossing the Cowpasture in Donally's Place at a Large Poplar on the River marked AC and BC.

The course beginning on the top of North Mountain continued to the Ohio, which it touched a little below Parkersburg. It was an exact parallel to the line between Rockbridge and augusta. It did not appear that the surveying of this line was ever carried beyond the summit of the Alleghany Divide.

From this old boundary between Augusta and Botetourt, the airline distance to Fincastle did not vary much from 35 miles, and was slightly less than the distance to Staunton. To the people of the Rockbridge area, the journey to a courthouse in 1777 was not excessively long. The need for a new county was very much less than in the case of Rockingham or Greenbbrier, all three of these counties being authorized by the same Act of Assembly, which was passed at the October session of 1777. The sections relating to Rockbridge were:

Section Three. And be it further enacted, that the remaining portion of the said counties and parishes of Augusta and Botetourt be divided into three counties and parishes, as follows, to wit, by a line beginning on the top of blue Ridge near Steel's mill, and running thence north 55 degrees west, passing the said mill, and crossing the North Mountain to the top, and the mountain dividing the waters of the Calfpasture front he waters of the Cowpasture, and thence along the said mountain, crossing Panther's Gap, to the line that divides the counties of Augusta and Botetourt, and that the remaining part of the county of Botetourt be divided, by a line beginning at Audley Paul's, running thence south, 55 degrees east, crossing James River to the top of the Blue Ridge, thence along the same, crossing James River, to the beginning of the aforesaid line dividing Augusta county, then beginning again at the said Audley Paul's, and running north 55 degrees west till the said course shall intersect a line to run south 45 degrees west, front he place where the above line dividing Augusta terminated. And all other parts of the said parishes of Augusta and Botetourt included within the said lines shall be called and known by the name of Rockbridge.

Section 4. (A court for Rockbridge, first Tuesday of every month, the first court to be held at the house of Samuel Wallace. The justices, or a majority of them, being present and duly sworn, shall fix on a place as near the center as the situation and convenience shall admit, and proceed to erect the necessary public buildings).

Section 5. Making it lawful for the governor with the advice of the Council to a point the first sheriff.)

Section 6. And be it further enacted, that at the place which shall be appointed for holding court in the said county of Rockbridge, there shall be laid off a town to be called Lexington, 1300 feet in length and 900 in width. And in order to make satisfaction to the proprietors of the said land, the clerk of the said county shall by order of the justices issue a writ directed to the sheriff commanding him to summon twelve able and discreet freeholders to meet in the said land on a certain day, not under five nor more than ten days from the date, who shall upon oath value the said land, in so many parcels as there shall be separate owners, which valuation the said sheriff shall return, under the hands and seals of the said jurors, to the clerk's office, and the justices, at levying their first county levy, shall make provision for paying the said proprietors their respective portions thereof, and the property of the said land shall on the return of such valuation, become vested in the Justices and their successors, one acre thereof to be reserved for the use of said county, and the residue to be sold and conveyed by the said justices to any persons, and the money arising from such sale shall be applied towards lessening the county levy; and the public buildings for the said county shall be erected on the lands reserved, as aforesaid. Section 7. (Relates to suits and petitions now depending. Dockets of such to be made out in Augusta and Botetourt.)

Section 8. (no appointment of clerk of the peace, nor of place for holding court, unless a majority of the justices be present.) (Another section dissolves the vestry of Augusta, and instructs the inhabitants of Augusta, Botetourt, Rockbridge, Rockingham and Greenbrier to meet at places appointed by their sheriffs before May 1, 1778, to elect twelve able and discreet persons as a vestry for each county.)

The boundaries of Rockbridge, as set forth in the above act, had since undergone but one change. In October, 1785, all the county west of the top of Camp Mountain was annexed to Botetourt.

The Cornstalk Affair

There was a belief that the killing of Cornstalk at Point Pleasant led to the establishment of Rockbridge. The perpetrators of that deed were some of the Rockbridge militia, and as there was an attempt to punish them, the trial would have been at the county seat of Greenbrier. The erection of a new county would insure a trial among friends and not among strangers. But the killing of Cornstalk took place 11 November 17777. It would have taken several weeks for the news to reach Williamsburg and for a movement to take shape in Rockbridge which would bear fruit in legislative action. The act authorizing Rockbridge had been passed in October of the same year.

The shawnees, "the Arabs of the New World," were a small but valiant tribe dwelling on the lower Sciot. In mental power they stood much above the average level of the red race, and it was an ordinary occurrence for a member of the tribe to be able to converse in five or six languages, including English and French. According to the Indian standard, the Shawnees were generous livers, and their women were superior housekeepers. They were so conscious of their prowess that they held in contempt the warlike ability of other Indians. It was their boast that they caused the white people ten times as much loss as they received. The most eminent war leader among the Shawnees was Cornstalk. it was not probable that he headed the band that struck Kerr's Creek. With slight loss to themselves, they killed, wounded, or carried away probably more than 100 of the whites. At Point Pleasant, the Shawnees were the backbone of the Indian army, and Cornstalk was its general-in-chief. It was only because of loose discipline in the camp that the Virginians were not taken by surprise. Technically, the battle was little else than a draw. Cornstalk effected an unmolested retreat across the Ohio, after inflicting a loss much heavier than his own. But his men were discouraged and gave up the campaign. Cornstalk was not in favor of the war, but was overruled by his tribe. During the short space that followed, he from time to time returned to Fort Randolph at Point Pleasant horses and cattle that had been lost by the whites or stolen from them.

In 1777 the Shawnees were again restless. They had been worked upon by British emissaries and white renegades. Cornstalk came with a Delaware and one other Indian and visited Fort Randolph under what was virtually a flag of truce. He warned Captain Arbuckle, the commandant, of the feeling of the tribesmen. His mission was an effort to avert open hostilities. According to the Indian standard, Cornstalk was an honorable foe, and he knew he ran a risk in putting himself in the power of the whites. Arbuckle thought it proper to detain the Indians as hostages. One day, while Cornstalk was drawing a map on the floor of the blockhouse, to explain the geography of the country beyond the Sciot, his son Ellinipsico hallooed from the other bank of the Ohio and was taken across. Soon afterward, two men of Captain William McKee's company, a Gilmore and a Hamilton, went over the Kanawha to hunt for turkeys. Gilmore was killed by some lurking Indian, and his body was carried back. The spectacle made his comrades wild with rage. They raised the cry of, "Let us kill the Indians in the fort," and without taking a second thought they rushed to the door of the blockhouse. They would not listen to the remonstrances of Arbuckle, and threatened his life. When the door was forced open, Cornstalk stood erect before his executioners and fell dead, pierced by seven or eight balls. His son and his other companions were also put to death. The slain chieftain was about fifty years of age, large in figure, commanding a presence, and intellectual in countenance. Good contemporary judges declared that even Patrick Henry or Richard Henry Lee did not surpass Cornstalk in oratory.

By the people of Kerr's Creek the raids into their valley were remembered with horror. Homes had been burned. Families had partially or wholly been blotted out. Women and children had been tomahawked and scalped. Friends and relatives had been carried away, and some of these had never returned. The scenes of 1759 and 1763 were referred to with more impatience than was usually found along what was once the frontier.

The Indian method of making war was unquestionably cruel. The impulses of the native were those of the primitive man. Like the chip, he was sometimes swept by gusts of passion. Deceit had ever been deemed legitimate in warfare. The Indian played the game without restraint and was consistent. The white man assumed to conduct war according to rules suggested by Christian civilization and laid down in time of peace. But in time of war he does not live up to these rules. It had been little more than a century since Cromwell had carried fire and massacre from one end of Ireland to the other, and with a fury that would have made Cornstalk "fit up and take notice." It was within theory of living men that the Highlanders of Scotland gave no quarter in their murderous clan fights. It seemed instinctive for nations of the Baltic stock to hold the colored races in contempt. To the frontiersman of america, the Indian was not only a heathen but an inferior. The comparatively humane treatment to which he thought the French and the British were entitled, because of their color, he held himself justified in withholding from the redskin. The practical effect of this double standard was mot unfortunate. It reacted with dire effect upon the white population. It was more often the white man than the Indian who was responsible for the cause of border trouble. The Indian's version was much less familiar to us than our own. Despite his proclivity to tomahawk the woman as well a the man, the child as well as the adult, the Indian in his war-paint was a gentleman when compared with the German soldier in the present war. The latter, who professes to be a civilized man, wars against the very foundations of a civilization that the red man knew next to nothing of. The Indian kept his word. He respected bravery. The children he spared and adopted he loved, and not infrequently the adult captive was unwilling to return to his own color. Women were never violated by the Indians of the tribes east of the Mississippi, and when a child was born in captivity to the white female, the mother was looked after as though she were one of their own kind.

The deed of Hall's men at Point Pleasant was a painful incident in Rockbridge history. It bore the same relation to open warfare, whether civilized or savage, that a lynching does to a fair trial in a courtroom. There was nothing to show that Cornstalk had anything to do with the killing of Gilmore, or that the perpetrator of that deed was a member of his tribe. Had Cornstalk been a British officer, his government would have pronounced his murder an inexcusable assassination, and would have avenged it with the execution of some captive American officer. The plea, which was not confined to the book by Kercheval, that it was right for the frontiersman to lay aside the restraints of civilization when dealing with the Indian, would, if it had been used in the present war, been made a justification for matching German atrocity by allied atrocity. Even at Point Pleasant, where we might expect the feeling against the native to be acute, it was long considered that the town lay under a curse. So late as 1807 it had only a log courthouse, 21 small dwellings, and a few ague-plagued inhabitants. It contained a monument to Cornstalk.

Only a few years since then, a contributor to one of the Lexington papers spoke rather harshly of Colonel roosevelt for mentioning the killing of Cornstalk as "one of the darkest stains on the checkered pages of frontier history." Roosevelt was no apologist for Indian cruelty. The wirier was probably unaware of the fact that Patrick henry, who was then governor of Virginia, denounced the deed in words that were much more vehement. He regarded it as a blot on the fair name of Virginia, and announced that so far as he was concerned, the perpetrators should be sought out and punished. Patrick Henry's efforts were nullified by the friends of the persons responsible.

In an attempt to avenge the death of their chieftain, the Shawnees besieged Fort Randolph in the spring of 1778. An Indian woman known among the whites as the Grenadier Squaw, and who was understood to be a sister to Cornstalk, and come to the fort with her horses and cattle. By going out of the stockade and overhearing the natives she was able to tell their plans to captain McKee, then the commandant. McKee offered a furlough to any two men who would make speed to the Greenbrier and warn the people. John Insminger and Joh Logan undertook the perilous errand, and started out, but not seeing how they could get past the Indians, they returned the same evening. John Pryor and Philip Hammond then agreed to go. The Grenadier squaw painted and otherwise disguised the men, so that they would look like Indians. The two messengers reached Donally's fort a few hours in advance of the Shawnees, and though a severe battle quickly followed, the foe was repulsed and the settlement was saved. | View or Add Comments (0 Comments) | Receive updates ( subscribers) | Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |