|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 14 , Issue 502012Weekly eZine: (374 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

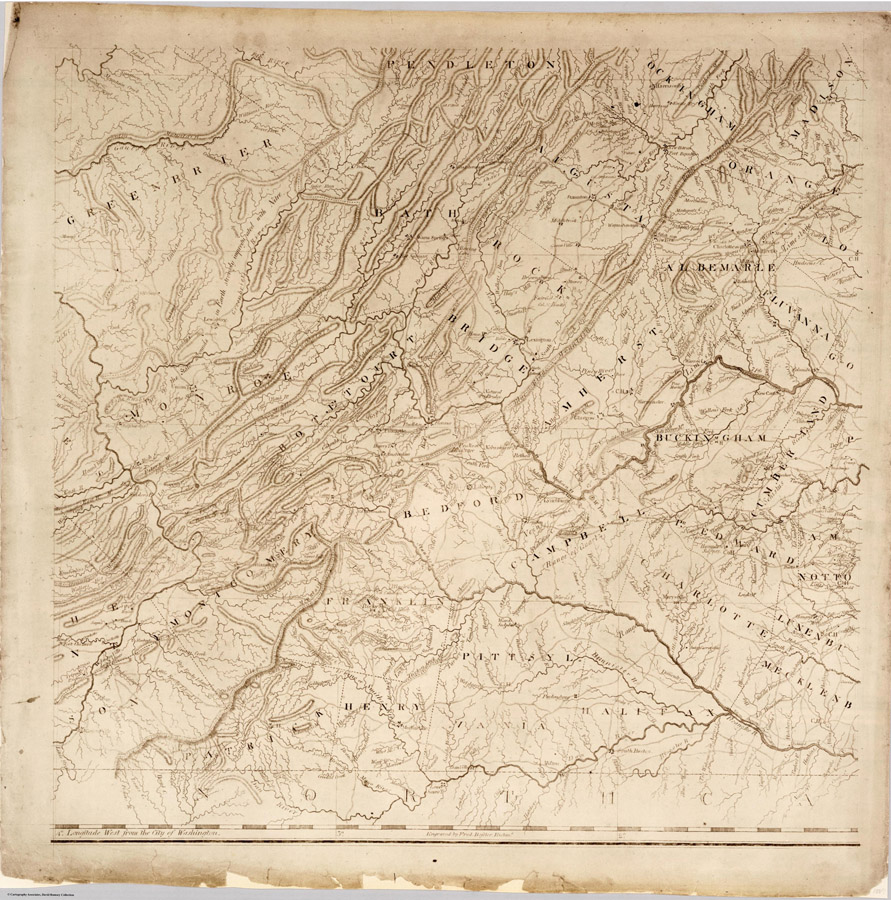

History of Rockbridge County, Virginia - Strife With The Red Man

This week we bring you more history of Rockbridge County, Virginia from Oren F. Morton's book published back in the 190-1912 era. We continue with Chapter VIII with the "Strife With the Red man." Rockbridge was a vacant land when found and explored by the whites. But there have always been inhabitants in America since a day that makes the voyage of Columbus seem as but an occurrence of the last years. In the Western Hemisphere as in the Eastern, we may be sure that war, or pestilence, or some other catastrophe hd here and there emptied a region of its human occupants.

The Indian mounds on Jump mountain opposite Wilson's Springs shows us the Indian path. There was also the stone-pile on North mountain. All these suppositions were not enough to account for the mound which used to stand on the Hays Creek bottom, a very short distance below the mouth of Walker's Creek. At the time it was dug away and examined by Mr. Valentine, it was almost circular, averaging sixty-two feet in diameter at the base and forty feet on the flat top. The vertical height was then four and one half feet, but the Gazette in 1876 spoke of it as having been ten or twelve feet high. The encroachments of cultivation had undoubtedly much diminished the original bulk. The excavators found eighty perfect skulls and more than 400 skeletons. In all instances the legs were drawn up and the arms folded across the breast. Shell-beads and pendants were found on the necks of twenty-eight of the skeletons. A few pieces of pottery and some other relics were found, and there were eight skeletons of dogs, several of these being almost perfect. The site was completely leveled back then, and the exact spot was in danger of being forgotten.

Those who knew something of the customs of the Red American, it was evident that this mound was a burial mound, and that near it was once a village. Indian huts were of very perishable materials, and it was not at all strange that no trace of the village can now be found, unless by a trained investigator. At the time of white settlement, about 1738, there may have been a very low earthing, marking the site of a palisade, and this could soon have been destroyed by repeated plowings. At all events, no recollection of such a ring seems to remain. How sad for this Indian history of Virginia.

White people were very prone to imagine that the native mounds were built over the corpses of the braves slain in battle. But the Indian war party rarely comprised more than a few dozen men, and often it was exceedingly small. The victors would lose but a few of their number, if any, and these were buried in individual graves marked by little mounds of loose stones. The vanquished dead were left to be devoured by wild beasts. It was to be remembered that until a recent time the European nations held themselves to be under no obligation to bury the dead of a defeated army. The fact that many of the skeletons in the Hays Creek mound were of women and girls, and the conventional mode of interment, show that the burials distributed over a considerable period of time. As to the age of the mound, there was no answer but conjecture. Earthworks tend to endure indefinitely, and in this instance the bones began to crumble on exposure to the air. This burial mound may have antedated the coming of the white man by several centuries.

A tradition of uncertain authenticity tells of a battle between Indians at the mouth of Walker's Creek. It further tells of a squaw who witnessed the fight from the end of Jump Mountain, and leaped over the precipice on seeing the fall of her companion. The tradition may be correct. The battle could not have resulted in the mound, though it may have resulted in the extinction of the village. The Indian's eyes were good, yet not keen enough to identify a man from the top of the precipice several miles away.

The Ulster people were very disputatious, particularly as to the meaning of texts from the Bible. An old resident of Hays Creek contended all his life as to the name of the tribe that built this mound. He made a solemn request ton e buried on the hill facing it, so that at the resurrection he might be the first one to see his theory vindicated.

Within the memory of men still living, a mound stood near Glasgow close to the position of the lowest county bridge on North River. On the Buffalo was a burial mound. No other earth mounds, extant or leveled have been named to the writer, Oren F. Morton. It was surprising that there was no knowledge of any mound on the bottom near Kerr's Creek postoffice. Such a spot would have appealed to the Indian as a place of settlement.

As to the mention of the stone heap on the summit of North Mountain, it stands close to the lexington and Rockbridge Alum Turnpike. it used to be twenty feet long, six feet wide, and four feet high, but the two holes dug into it have lowered the height and disarranged the once nicely rounded top. The pieces of rock were wholly of brown ironstone, such as was found abundantly on the western face of the mountain. Isaac Taylor, a Rockbridge man who went to Ohio, was told by an Indian that it was the work of a war party from the West. Each brave, while passing over, was to throw down a stone, and on the return each survivor was to pick one up, so that a count of the remaining ones might determine the loss. The expedition was disastrous and the heap remained quite intact. If the tradition be correct, it must apply to some other and smaller stone-pile. Before being tampered with, this mound must have contained several thousands of rock fragments. Much more reasonable was the conjecture that it grew up little by little, and was due to a custom of the passing red man to drop a stone as an act of propitiation to the Great Spirit, and as the expression of a wish that his journey might have a favorable outcome. It was in fact a practice of the red man to rear a mound where his trail went through a mountain pass. This pass was used by him and when the trees were leafless it commanded a view of the Kerr's Creek valley.

When the white explorer came the Rockbridge area, like the Valley of Virginia in general, was largely occupied by tracts of prairie. These were known as Indian meadows, or as savannas, the word prairie having not yet come into the English language. These meadows were fired at the close of each hunting season so as to keep back the forest growth and thus attract the buffalo and other large game. This practice had undoubtedly been going on for centuries. Throughout all Appalachia nature strives to keep the surface clothed in forest. A large expanse of open ground could only originate in the little clearing that always surrounded the native village. The persistent firing of a deserted clearing would make the meadow steadily increase in size.

After white settlement began, parties of Indians continued to come here to hunt, or to pass through on some war expedition. The Iroquois of New York were the native claimants of the district, and they were at feud with the Cherokees and Catawbas to the southward. Hunting parties would build bark cabins for temporary shelter, and these were sometimes temporarily used by the whites.

John Craig was for a third century the minister at the North Mountain Meeting House near Staunton. He lived five miles away and walked to church carrying his gun on his shoulder. he wrote that the Indians "were generally civil, though some persons were murdered by them about that time (1740). They march about in small companies from fifteen to twenty, and must be supplied at any house they call at, or they become their own stewards and cooks, and spare nothing they choose to eat and drink."

While the Indian was hunting, he took food wherever he found any, and he considered that animals running at large were lawful game. If he expected free and liberal entertainment, it was because he was ready to treat others as he expected to be treated himself. There were no bounds to his hospitality, because in the usage of his race food was not private property.

But the points of view of the two races were very divergent. The native thought the paleface uncivil and inhospitable, and was not attracted to his manner of living. Neither did he like being elbowed step by step out of the hunting ground which for generations had belonged to his fathers. The white man despised the Indian as a heathen and was contemptuous of his rights. He regarded him as a thief and wished he would keep out of the way. He deemed it "contrary to the laws of God and man for so much land to be lying idle when so many Christians needed it." But notwithstanding the sources of distrust, the tribesmen were in a general way friendly until 1753. They learned to express themselves in English, and it was significant that they became very familiar with terms of insult and profanity. In their own languages there were no "cuss words," and they did not comprehend the real nature of them.

The first clash between the settler and the aborigine took place near the mouth of North River, 18 December 1742. The information as to the cause of it is meager and obscured, though. The current account was the one written by Judge Samuel McDowell, sixty-five years after the time of the tragedy. But the judge was only seven years old when it occurred, and the most definite impression made on his mind was the sight of the lifeless bodies of his father and the other men who were killed, after they had been brought to Timber Ridge for burial. In a practical sense, his knowledge of the matter was derived from older persons and not until he had reached a mature age.

The judge related that thirty-three Iroquois came into the Borden tract on their way to fight the Catawbas, and gave the settlers some trouble. They were entertained a day by Captain McDowell, who plied them with whiskey. They then went down South River, lay in camp seven or eight days, hunted, took what they wished, scared the women, and shot horses running at large. Complaint being made, Colonel Patton ordered McDowell to call out his militia company, and conduct the Indians beyond the settled area. McDowell took about thirty-four men, these being all the county could furnish. Meanwhile, the Iroquois moved farther southward. McDowell overtook them and conducted them beyond Salling's, then the farthest plantation. One Indian was lame and fell behind, all but one of the militia passing him. This man fired upon the native as he went into the woods. The native then raised the war-cry, and the fight was on. The Indians at length gave way, took to the Blue Ridge, and followed it to the Potomac. Seventeen of them were killed, several others died on the retreat, and only ten got home. O fate militia, the killed were eight or nine. Jacob Anderson, Charles Hays, Joseph Lapsley, Solomon Moffett, and Richard Woods were in the battle.

Another and more trustworthy version was that which was unearthed by Mr. Charles E. Kemper front he colonial records of Pennsylvania and New York. This account states that Colonel Patton reached the battlefield three hours after the fight. He wrote that very day to the governor of Virginia, reciting the particulars and asking his intervention to avert a war. That official wrote to the governor of New York, enclosing Patton's letter. This letter recounts that the Indians had appeared int he settlements in a hostile manner, committing the annoyances already spoken of; that on coming up with them, McDowell and Buchanan sent forward a man with a signal of peace, upon whom the Indians fired, precipatating a fight that lasted forty-five minutes. Eleven whites were killed and others wounded, and eight or ten Indians were killed. The governor of New York sent an agent to see the Iroquios, who claimed the Valley of Virginia by right of conquest. The Indians were restive and the authorities were apprehensive of trouble. The Governor of Pennsylvania undertook to act as mediator. An Indian who was in the fight told him his party consisted of thirty-two Onondagas and seven Oncidas. They were treated well while passing through Pennsylvania, but in Virginia they were given nothing to eat and had to kill a hog one in a while. As they went up the Valley they were several times interfered with by the whites, but avoided difficulties with them. They rested a day and two nights near the spot where the fight took place. On resuming their march, some of the militia, riding horseback, fired on two boys but did not hit them. The Indian leader told his men not to fire because of the white flag. But the whites fired again, idling two of the party. The chief then ordered an attack, and the Indians fought with tomahawks at close quarters. Two of their number were killed and five wounded. The whites were worsted, then of them being killed. Ten of the Indians went up the river to the mountains,and were pursued to the Potomac, barely escaping with their lives. The mediator ruled that the whites were the aggressors, and by way of reparation Governor Gooch paid the Iroquois 100 pounds. The trouble was finally adjusted by the treaty of Lancaster in 1744, the Iroquois then renouncing their claims to Virginia.

In suit for slander brought by James McDowell against Benjamin Borden, Jr., and which was decided in favor of the defendant, there was an obscure allusion tot he responsibility for the affair. According to McDowell, Brden applied these words to him, August 17, 1747: "Thou art a rogue and a murdering villain and I can prove it. He is a murderer and brought the Indians upon the settlement." Thirteen claims for losses by the Indians were presented in the February court of 1746. Among the claimants were Isaac Anderson, Domick Berrall, Jospeh Coakton, Henry Kirkham, Joseph Lapsley, John Mathews, Francis McCown, John Walker, James Walker, and Richard Woods.

The following was the roster of John McDowell's company. Not all these men were in the battle:

Aleson, John; Beaker, Hen; Cambell, Gilbert; Cambell, James; Cares, John; Corier, John; Cunningham, Hugh; Cunningham, James; Dredin, David; Finey, James; Finey, Michael; Gray, John; Hall, William; Hardiman, James; Kierkham, Hen; Lapsley, Jospeh; Long;, Long; Mason, Loromer; Matthews, John; McClewer, Alexander; McClewer, Holbert; McClewer, John; McClure, Alexander; McClure, Moses; McCowen, Fran; McDowell, Ephraim; McDowell, James; McKnab, Andrew; McKnab, John; McKnab, Patt; McRoberts, Samuel; Miles, William; Miless, John; Miller, Michael; Moore, James; Patterson, Edward; Patterson, Erwin; Quail, Charles; Rives, David; Saley, John Peter; Taylor, Thomas; Whiteside, Thomas; Wood, Richard; Wood, Samuel; Wood, William; Young, Robert; Young, Matthew.

The French and Indian war broke out in 1754, and continued, so far as the Indians were concerned, until 1760. The advance line of settlement and passed the Alleghany divide, and the greatest havoc was int he valleys along the frontier. A local cause for the outbreak was the outrage at Anderson's barn on Middle River. The date was not exactly known, but seems to be the month of June, 1753, or possibly 1754. Twelve Indians were returning from a raid against the Cherokees, and lodged with John Lewis near Staunton. Some men were present whose families or friends had suffered some loss at the nada of the natives. A beef was killed and whiskey provided. The guests were induced to stay till nightfall and give one of their dances. After they left they were followed int he darkness to Anderson's barn, where all but one were murdered. For this act of treachery in a time of at least nominal peace, a heavy toll of vengeance was exacted. The colonial government sought to punish the perpetrators, but the effort was ineffectual. One of the faults of the Ulstermen was their propensity to make trouble with the heathen.

The Rockbridge area was by no means safe from attack, and there were several blockhouses for the protection of the people. William Patton mentioned a stockade at Alexander McClary's, a mile and half from his home, and said there were several others int he Borden grant. One of these must have been the Bell house, which was still standing and occupied.

It was about two miles south of Raphine and very near a branch. Another was a log structure on Walker's Creek, used as a dwelling until a recent date. The floor was of walnut puncheons. The roof, which was too steep to scale, fell in during the winter of 1917-18. In several other instances, the pioneer blockhouse still existed, with widened windows and some other alteration, or the logs had been used in a building of later design. In all instances, the walls and doors were bullet-proof against the weapons of that age, the windows were too narrow for akan to crawl through, and there were loopholes int he walls. The loophole was cut int he shape of the letter X, so that a considerable breadth of vision might be commanded by the gun pointed through the opening. A spring or other water supply was always within easy distance. In some instances the water was reached through a covered way, which was practically narrow tunnel, high enough for a person to pass through. The Indian was unwilling to storm a blockhouse. The cost might be severe, and the defenders were comparatively safe from his bullets. So he endeavored to gain his end by stealth or stratagem, and when he did make an attack it was usually by night. If he could set fire tot he roof he did so.

A council of war held at Staunton, May 20, 1756, mentioned that "the greatest part of the able-bodied single men of this county is now on duty on our frontiers, and there must continue until they are relieved by forces from other parts." Sitting on this council were these captains: Joseph Culton, John Moor, Joseph Lapsley, Robert Bratton, James Mitchell, and Samuel Norwood.

The only conspicuous raids belonging to this period were the occurrences in the Renick settlement and the first foray into the valley of Kerr's Creek.

The date of the attack on the Renick house was July 25, 1757. A party of Shawnees, said to have been sixty in number by probably much fewer, came through Cartmill Gap to Purgatory Creek, where they killed Joseph Dennis and his child, and took prisoner his wife, Hannah. They also killed Thomas Perry. Then they went to the house of Robert Renick, where they captured Mrs. Renick, her four sons, and a daughter. The next blow was at Thomas Smith's, where they killed both Renick and smith, and took away Mrs. Smith and her servant, Sally Jew. George Mathews, Audley Maxwell, and William Maxwell, who then were young men, were on their way to Smith's, and thought a shooting match was in progress. As soon as they saw the bodies of the two men, they wheeled their horses about,a nd the four bullets fired at them at the same instant did no other harm than to wound Audley Maxwell slightly and take off the club of Mathews' queue. One part of the Indians started away wight he prisoners and booty, and the others went to Cedar Creek. An alarm was given and the people of the neighborhood gathered at Paul's stockade near the site of Springfield. The women and children were left with a guard of six men, while George Mathews went in pursuit with a force of twenty-one men. He overtook and fought the enemy, but the night was wet and dark, and the foe got away. Next morning nine dead Indians were found on the battleground and were buried. Benjamin Smith, Thomas Maury, and a Mr. Jew were killed, and were buried in the meadow of Thomas Cross near Springfield. Mrs. Renick was released a few years later. Her daughter died in captivity, and her son Joshua became a chief of the Miamis. The other children returned with their mother. Mrs. Dennis was a woman of much resourcefulness and determination. She learned the Shawnee tongue, painted as the red men did, and because of her skill in treating illness she was given much liberty. She thereby found a chance to escape, crossed the Ohio on a driftwood log, and made her way back to her frontier home. This was in 1763.

It si very probable that several minor raids took place, no clear recollection of which had been handed on to the present day. An occurrence can easily be given a wrong setting by its being accidentally merged with some larger event. Sometimes a dingle Indian would go on the warpath for himself, and when the party was very small only depredations on a small scale were likely to be committed. There were instances where some white scoundrel would disguise himself as an Indian and perpetrate an outrage. Such may be the explanation of the tragedy at the home of John Mathews, Jr., the nature e of which recalls the Pettigrew horror of 1846. Sampson Mathews made oath that his brother John, with his wife and their six children, were burned to death in their house. A neighbor named Charles Godfrey Milliron was arrested on suspicion and held for trial at the capital. Milliron seemed to have been acquitted, but the results were unknown.

An incident which took place in Botetourt was worthy of mention, when Robert Anderson and his son William, grandfather to William A. Anderson of Lexington, went to a meadow to look after some livestock, and passed the night in a log shelter, the door of which could be strongly barred. Before morning Mr. Anderson woke up and roused his son, telling him the animals were restless and that he feared Indians were near. Bear oil and cabin smoke gave the redskins an odor that was quickly noticed by domestic animals. Voices were presently heard, and father and son held their weapons in readiness for an emergency. The prowlers tried the door, and seeing it did not readily yield, they used the pole as a battering ram, but without visible effect. Much tot he relief of the persons within they then desisted and went away. In the morning it was seen that another blow would have forced the door.

The red terror threatened to depopulate the Valley of Virginia and the settlements beyond. Writing in 1756, the Reverend James Maury made this observation: "Such numbers of people have lately transported themselves into the more Southerly governments as must appear incredible to any except such as have had an opportunity of owning it. By Bedford courthouse in one week, 'tis said, and I believe, truly said, near 300 inhabitants of this Colony past on their way to Carolina. From all the upper counties, even those on this side of the Blue Hills, great numbers are daily following."

What is known as the Pontiac war broke out very suddenly in June, 1763, and continued more than a year. It was a concerted effort, on the part of a confederacy of tribes, to sweep the whites out of the country beyond the Alleghanies. To a band of Shawnees was assigned the task of operating in the Rockbridge latitude. Their first blow completely destroyed the Greenbrier settlements, and their next attention was given to Jackson's River and the Cowpasture. Thence a party crossed Mill and North mountains to devastate the valley of Kerr's Creek.

there were two raids into this locality and there had been some doubt as to their chronological sequence. That one of them took place July 17, 1763, is evident. There was agreement as tot he day and month of the other event; October 10th. Samuel Brown said the second raid occurred two years after the first, and he placed it in 1765. In this he is followed doubtfully by Waddell in his "Annals of Augusta." Mr. Brown wrote his account a long while ago, and when people were living whose knowledge of the massacres was very direct. nevertheless, he was in error. His informants were confused in their recollection of dates.

The record books of Augusta contain no hint of any Indian trouble in the fall of 1764 or 1765. A raid of serious proportions would have constituted a renewal of the Pontiac war, and further military events would be on record in frontier history. But in 1759 and 1760 the number of wills admitted to record, the number of settlements of estates, and the number of orphan children put under guardianship was deeply significant. However, our evidence was more conclusive. In the suit of Thomas Gilmore against George Wilson, recorded November 19, 1761, the plaintiff makes this declaration: "During the late war the Indians came to the plantation where plaintiff lived, and after killing his father and mother, robbed them and plaintiff of almost everything they had. Defendant and several others pursued the Indians several days and retook great part of the things belonging to the plaintiff. The inhabitants of Car's Creek, the plaintiff not being one of them, offered to any persons that would go after the Indians and redeem the prisoners, they should have all plunder belonging to them."

The records further tell us that John Gilmore (my 6th great grandfather) was dead in 1759 and that Thomas Gilmore was his executor. We may therefore affirm that the earlier raid occurred October 10, 1759, and the later, July 17, 1763.

With respect to the first there was a forewarning. Two Telford boys, returning from school, reported seeing a naked man near their path. Little serious thought seems to have been given to the matter. A few weeks later, twenty-seven Indians were counted from a bluff near the head of the creek. The war party first visited the home of Charles Dougherty and killed the whole family. The wife and a daughter of Jacob Cunningham were the next victims. The girl, ten years of age, was scalped, but made a partial recovery. Four Gilmores and five of the ten members of Robert Hamilton's (my 7th great grandfather) family were afterward slain. The Indians did not go any farther. Accounts differ as to whether any prisoners were taken by them. They killed twelve persons, and according to one statement, thirteen were carried away.

With his usual promptness and energy, Charles Lewis, of the Cowpasture, took the lead in raising three companies of militia, one headed by himself, the others by John Dickenson and William Christian. The Indians were overtaken near the head of Back Creek in Highland county. It was decided to attack at three points. Two men sent in advance were to fire if they found the enemy had taken alarm. They came upon two of the enemy,one leading a horse, the other holding a buck upon it. To avoid discovery the scouts fired and Christian's company charged with a yell. The other companies were not quite up and the Indians escaped with little loss. However, they were overhauled on Straight Fork, four miles below the West Virginia line, their camp being revealed by their fire. All were killed except one, and the cook's brains were scattered into his pot. Their carrying poles were seen here many years later, and accent guns have been found. In the first engagement the loot was recovered, and it was sold.

On the second visitation the Indians were in greater force,and made their approach more cautiously. They concealed themselves a day or two at a spring near the head of Kerr's Creek. But moccasin tracks were noticed in a cornfield, and some men detected the camp form a hill. A rumor had come tot he settlement that Indians were approaching, but there was little uneasiness. It is nearly certain that the savages first seen were an advance party, and that this was waiting for a reenforcement. Another probable motive for delay in an attack was to scare the settlers into gathering at some rendezvous, so that they might be fallen upon in a mass. If such was the purpose it was accomplished. The people flocked to the blockhouse of Jonathan Cunningham at Big Spring.

Meanwhile the house of John McKee was attack and Mrs. McKee was unable to walk fast, and she insisted that her husband should go on and effect his own escape. Before doing so he hid her in a sinkhole filled with bushes and weeds, but the barking dog betrayed the place of concealment. After the redskins had gone on, she was taken to the house, where she soon died. This statement was challenged by the author of "The McKees of Virginia and Kentucky." He on trues it as a reflection on John McKee's courage and his duty to his wife. he said that some of the settlers did not like this pioneer for his bluntness, and that they set afloat a garbled version of the facts. The author of the book preferred to believe that John McKee had gone to a neighbor's to look after some sick children, and finding on his return that his wife was scalped, he took her to the house. The murder could not have occurred in the first raid, as some statements affirm. The family Bible gives July 17, 1763, as the date of Mrs. McKee's death.

We could go further with more stories of the Indians and their interactions with the European settlers, but we shall save that for the next few weeks so this feature doesn't get to lengthy. Come back in the next few weeks as we learn about our Virginia ancestors that settled in the Rockbridge county area.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments)

| Receive

updates ( subscribers) |

Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |