|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 17 , Issue 172015Weekly eZine: (374 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

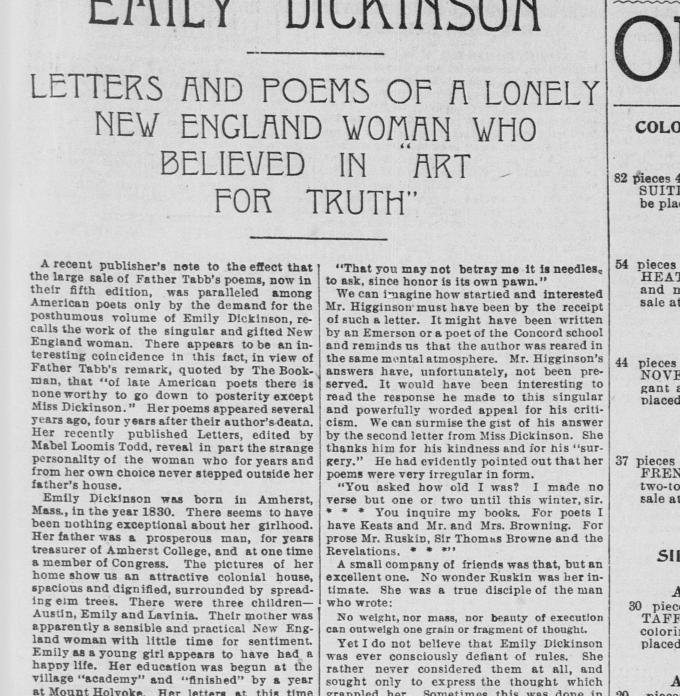

Emily Dickinson Believed In "Art For Truth"

This news article appeared in The San Francisco Call, Sunday September 20,, 1896: Letters And Poems Of A Lonely New England Woman Who Believed In "Art For Truth". Of the late American poets there was none worthy to go down to posterity except Emily Dickinson.

Dickinson's poems appeared several years (four years) after their he death. Emily's recently published letters, edited by Mabel Loomis Todd, revealed in part the strange personality of the woman who for years and from her own choice never stepped outside her father's house.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Mass., in the year 1830. There seems to have been nothing exceptional about her girlhood. Her father was a prosperous man, for years treasurer of Amherst College, and at one time a member of Congress. The pictures of her home show us an attractive colonial house, spacious and dignified, surrounded by spreading elm trees. There were three children - Austin, Emily and Lavinia. Their mother was apparently a sensible and practical New England woman with little time for sentiment. Emily as a young girl appears to have had a happy life. Her education was begun at the village academy and finished by a year at Mount Holyoke. Her letter at this time are the letters of the average schoolgirl and show no trace of the epigrammatic transcendentalism which marks them later.

Neither is there any trace of the shyness which became a passion in her after life of her mates and lived the normal life of the young woman of that time. Her early friend, Mrs. Ford, to whom some of her letters are addressed, prefaces their publication by a short sketch of Emily's girlhood. According to Mrs. Ford when was one of a circle of talented young girls, several o whom became famous in after years. Fanny Montague, the art critic, was one, and another was Helen Fiske, who wrote under the pen name, H. H., and whose death in San Francisco a few years before was a sad loss to American letters.

Emily Dickinson strong to say, was the wit of the group and furnished the funny items for the school paper. The only hint she gave her friend of her future strange aloofness from her fellows was by asking her one day if it did not make her shine to hear some people talk as though they took all the clothes off their souls. Not until she is about 20 do we find symptoms of that later malady - if malady be the word for her almost fierce seclusion.

The friend who most helped to form her girlish aspirations was a teacher in the academy, a Mr. Leonard Humphrey, who was a few years older than herself. He was a graduate of Amherst and had showed unusual intellectual ability and penetration. A letter to a friend at this time briefly records his death. His name is only mentioned twice in the course of her whole correspondence and once in a letter to her literary godfather, Mr. Higginson. She says, "My dying tutor told me he would like to live till I had been a poet."

This was twelve years after his death. we cannot help wondering whether this was not the key of those minor cadences to which her life was henceforth set. It seems almost a sort of sacrilege to try to pierce that reserve in which she veiled herself. There are souls as tremulous as sensitive plants. A year later in a letter to the same friend she declines a proffered invitation, saying: "I don't go from home unless emergency leads me by the hand, and then I do it obstinately and draw back if I can."

There is no hint as yet of her writing poetry. About this time her brother, Austin, left home and college to take a position in Boston. Her letters to him are delightfully clever, full of wit, with an undercurrent of sadness and loneliness, ostensibly because of his being gone. In these letters we begin to detect the beat of words, the sense of cadence which marks her poetry rather than perfect rhyme or meter. Even in homely sentences one perceives the writer to have that ear for words which is somewhat rarer than an ear for music. However, ti need not take a very maker to write in that manner. This fragment from a letter to her cousin, on the death, in his first battle, of a friend's son, suggests the poet:

- "Poor little widow's boy, riding tonight in the mad wind, back to the village burying around, where he never dreamed of sleeping. Ah, the dreamless sleep."

Emily's letters to her brother detail the family and neighborhood doings, with here and there a suggestion of her growing dislike of meeting people. She mentions a great village fete on the opening of the new railroad.

Emily's letters to her young cousins in the beginning of the second volume show the womanly and affectionate side of her nature, that had no warp in its attitude toward those she loved.

With Emily's constantly increasing seclusion the necessity for some expression seemed to grow. She made no occupation of writing, but while busy with her house duties or her sewing - for she was pre-eminently a practical, capable New England woman - she would jot down the thoughts that came to her in fragments of verse, writing them often on the margin of newspapers or the backs of old envelopes. There was no system or order in her procession and no thought of publication.

Any sort of publicity would have been unbearable to the woman, whose shrinking from the eyes of strangers was so great that she resorted to all sorts of devices to avoid addressing her letters in her own hand.

Sometimes she used newspaper labels, or if these were not to be had, one of the family performed the office for her. Her penmanship, seemed characteristic of her isolation, each letter standing alone. Writing for herself alone it was not to be expected that her verses should be finished in form.

Indeed it was doubtful whether she understood anything of the theory or technique of poetry. But, as one of her critics said, "When a thought takes our breath away, a lesson in grammar seems an impertinence." Though her poems may be fragmentary in form, they are never so in substance. Each contained a distinct thought.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments) | Receive updates ( subscribers) | Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |