|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 17 , Issue 62015Weekly eZine: (374 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

History of St. Valentine's Day (Ancient Greek , Pre-Roman Festival)

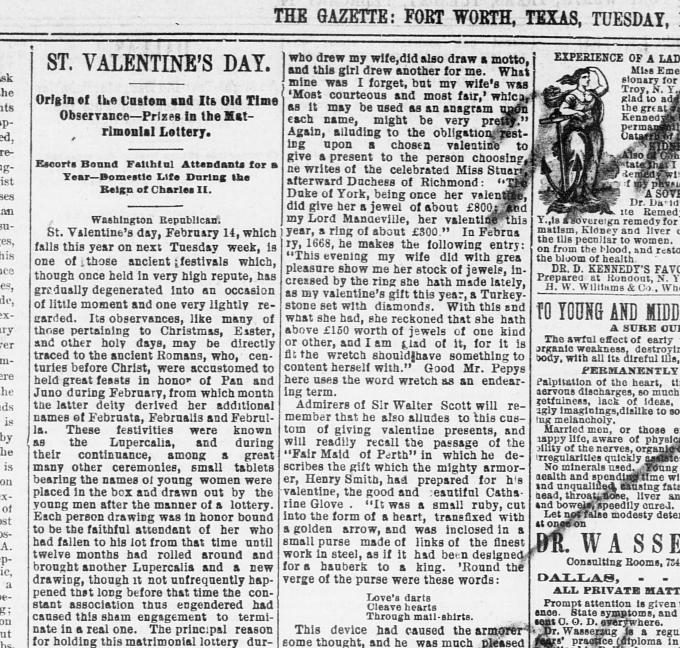

It was 14th of February 1888, page 3, Fort Worth Daily Gazettethat we found this mention of the origin of the custom and its old time observance of St. Valentines Day.

St. Valentine's day, February 14, 1888, which fell on a Tuesday, was one of those ancient festivals which, though once held in very high repute, had gradually degenerated into an occasion of little moment and one very lightly regarded. Its observances, like many of those pertaining to Christmas, Easter, and other holy days, may be directly traced to the ancient Romans, who, centuries before Christ, were accustomed to holding great feasts in honor of Pan and Juno during February, from which month the latter deity derived her additional names of Februata, Februalis and Februlla.

These festivities were known as the Lupercalia, and during their continuance, among a great many other ceremonies, small tablets bearing the names of young women were placed in the box and drawn out by the young men after the manner of a lottery. Each person drawing was in honor bound to be the faithful attendant of her who had fallen to his lot from that time until twelve months had rolled around and brought another Lupercalia and a new drawing, though it not infrequently happened that long before that time the constant association thus engendered had caused this sham engagement to terminate in a real one. The principal reason for holding this matrimonial lottery during the festivities of the Lupercalia was because they were celebrated at a time of the year when, it was popularly believed, the birds selected their mates, a tradition that was still attached to St. Valentine's Day in 1888.

This notion was referred to by Shakespeare in his "midsummer Night's Dream," act IV, scene I, where he makes Theseus say: "St. Valentine is past; Begin these wood birds but to coupe now."

When Christianity shed its first luminous rays over the pagan hearts of ancient Rome the early fathers encountered one of their hardest tasks in endeavoring to crush out heathen superstitions and in trying to induce the people to abandon heathen festivities. They found that the best means of accomplishing this latter end was to divert all such observances of undue solemnity while retaining all their social aspects and associating them either remotely or directly with some person or thing pertaining to the church. For the festivities of the Lupercalia they substituted those of St. Valentine's Day, thereby retaining the date of the ancient festival and at the same time connecting it with Christianity through a great saint who suffered martyrdom in the third century, being first beaten with clubs and then beheaded while a priest of Rome, where his remains how rest in the church of St. Haxedes, and where a gate, now known as the Porta del Popolo, was formerly called, in his honor, the Porta Valentini.

When it was considered that this excellent man never, either directly or indirectly, bore any relation whatever to the observances and ceremonies peculiar to the day devoted to him, it seemed very strange that his name should have come to be applied to sweethearts and to the written, printed, and painted amatory addresses which they were annually accustomed to exchange, as well as to the highly colored comical and satirical woodcuts, white a few lines of doggerel printed beneath them, which were so liberally displayed in the stationers' windows at this time.

It had been stated that it was from the fact that St. Valentine was renowned for his universal love and charity, that the custom of choosing love partners upon his day and calling them by his name took tis rise, but this idea was long since exploded. It was in 1888 well known that the only reason why these observances were associated with St. Valentine was the one already given -- that the early fathers desired to Christianize the heathen festival of the Lupercalia, and to have it fall upon a sacred day of approximate date.

The good churchman found it impossible to persuade the common people to entirely abandon any ceremony to which they had become deeply attached. Despairing, therefore, of abolishing the matrimonial lottery of the Lupercalia, they modified its form and endeavored to give it a religious character by substituting the names of particular saints to be drawn as valentines instead of the names of men and women. From this ancient usage was derived the custom, still occasionally observed in some Catholic countries, of selecting on ST. Valentine's Day for the ensuing year a patron saint, who was called a valentine. But the young men and maidens, finding little amusement in drawing out the names of dead and gone saints, soon relapsed into their old custom of drawing each other and even at the present time in many of the rural districts of England and Scotland it was customary on the eve of St.

Valentine's Day for the young people of both sexes to draw lots for a valentine. As the men drew from a bag containing the names of the maids while the latter drew from one containing the names of the men, it generally happened that each person had two valentines, but the young men regarded themselves much more strongly bound to the valentines they had drawn than to the one who had drawn them. If, as sometimes happens, a young man and woman should each chance to draw the other, it was regarded as absolutely certain that they were destined to wed, and must not, under any circumstances permit their attention or affection to centre elsewhere.

During the reign of Charles II, as we learn from that most interesting and curious record of the domestic life of that period preserved for us in the diary of Mr. Pepys, married people were equally eligible with single ones for the lottery of St. Valentine's Eve, and anyone chosen as a valentine was in honor bound to give a present to the person choosing him or her. On St. Valentine's Day, 1667, Mr. Pepys wrote, "This morning came up to my wife's bedside (I being up dressing myself) little Will Mercer to be her valentine, and brought her name written upon blue paper in gold letters, done by himself very pretty, and we were both well pleased with it. But I am also this year my wife's valentine, and it will not cost me, but that I must have laid out if we had not been valentines."

Admirers of Sir Walter Scott would remember that he also alludes to this custom of giving valentine presents, and would readily recall the passage of the "Fair Maid of Perth" in which he describes the gift which the mighty armorer, Henry Smith, had prepared for his valentine, the good and beautiful Catharine Glover, "it was a small ruby, cut into the form of a heart, transfixed with a golden arrow, and was inclosed in a small purse made of links of the finest work in steel, as if it had been designed for a hauberk to a king. 'Round the verge of the purse were these words: Love's darts Cleave hearts Through mail-shirts.

This device and caused the armorer some thought, and he was much pleased with his own composition, because it seemed to imply that his skill could defend all hearts, saving his own.

In many parts of England and Scotland it was still customary, as it had been for many centuries, for young men and women to regard as their valentine the first person of the opposite sex whom their eyes behold on the morning of St. Valentine's day, and they had the right to claim the said valentine with a kiss, which he or she was in honor bound to accord without resistance or remonstrance of any kind, Scott, in his novel of "The Fair Maid of Perth," already quoted, beautifully describes the manner in which the peerless Catharine Glover thus claimed the hold armorer, Henry Smith, as her valentine, after he had saved her from dishonor by his great valor and strength, on St. Valentine's Eve.

The English poet Gay also alludes to this custom as follows: "Last Valentine, the day when birds of kind their paramours with mutual chirping and, I early rose - just at the break of day -- Before the sun had chased the stars away; A field I went, amid the morning dew To milk my kine (for so should housewives do), Thee first I spied -- and the first swain we see, In spite of fourteen shall our true love be."

Shakespeare also alludes to this custom in "Hamlet," where poor Ophelis sings:

"To-morrow is St. Valentine's Day,

All in the morning bedtime,

And I, a maid at your window,

To be your valentine."

It was in a series of quaint essays published in 1754-6, one who signs herself "A Forward Miss," thus writes on some of the observances of this occasion: "Last Friday was Valentine's Day, and the night before I got five bay leaves and pinned four of them to the four corners of my pillow and the fifth to the middle, and then, if I dreamed of my sweetheart, petty said we should be married before the year was out. But, to make it more sure, I boiled an egg hard and took out the yolk and filled it with salt, and, when I went to bed, ate it, shell and all, without speaking or drinking after it. WE also wrote our lovers' names upon bits of paper,a nd rolled them up in clay and put them into water, and the first that rose was to be our valentine. Would you think it? Mr. Blossom was my man. I lay abed and shut my eyes all the morning till he came to our house, for I would not have seen another man before him for all the world."

The custom of exchanging amatory addresses between valentines on St. Valentine's Day is a very old one. Chaucer had left some quaint models of this style of composition, as had also the poet Lydgate, who died in 1440. A famous writer of these valentines was Charles, Duke of Orleans, who was taken prisoner at the battle of Agincourt. Drayton, a poet of Shakespeare's time, whose works, though now almost forgotten, abound in passages of rare beauty, writes thus charmingly of his valentine:

My lips I'll softly lay

Upon her heavenly cheek,

Dyed like the dawning day,

As polish'd ivory sleek;

And in her ear I'll say,

"Oh thou bright morning star

"Tis I have come so far

My valentine to seek.

Each little bird, this tide,

Doth Choose her loved peer,

Which constantly abide

In wedlock all the year,

As nature is their guide;

So may we two be true

This year, nor change for new,

As turtles coupled were."

In comparison with such verses as these, the so-called poetry of the sentimental valentines sold in stationers' shops must pale its ineffectual fire. One of the best possible descriptions of these latter productions was given by Dickens in his "Pickwick Papers," where he tells how Sam Weller, on gazing into a stationer's window on St. Valentine's Eve, behold "a highly colored representation of a couple of human hearts skewered together with an arrow, cooking before a cheerful fire, while a male and female cannibal in modern attire -- the gentleman being clad in a blue coat and white trousers, and the lady in a deep red pelisse with a parasol of the same -- were approaching the meal, with hungry eyes, up a serpentine gravel path leading thereunto. A decidedly indelicate young gentleman, in a pair of wings and nothing else, was depicted as superintending the cooking. A representation of the spire of the church in Langham place appeared in the distance, and the whole formed a valentine."

But even the sending of valentines, the only observance of St. Valentine's Day that is retained in our own land and time, seems to e gradually dying out. For some years past it had been the testimony of postmasters all over the country that the number of these sentimental missives passing through the mails had steadily decreased. This falling off began with eh introduction of Christmas, New year and Easter cards, the number of which transmitted by post had increased just i proportion to the falling off in valentines. The reason for this was obvious. A sentimental valentine, the only one for which the word was not a misnomer, can only have its proper significance when it passes between persons of opposite sex. A Christmas, New Year or Easter car, on the contrary, is universal in its applicability. It is equally appropriate and acceptable from mother to daughter, form sister to sister, from over to sweetheart, from friend to friend. Good wishes on any of those festal occasions, Christmas, New Years or eAster, may very gracefully and appropriately be sent by anybody to anybody, and the popularity of these three classes of cards bids fair to finally extinguish even the last remaining observance of the day devoted to the honor of good St. Valentine.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments)

| Receive

updates ( subscribers) |

Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |