|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 15 , Issue 172013Weekly eZine: (374 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

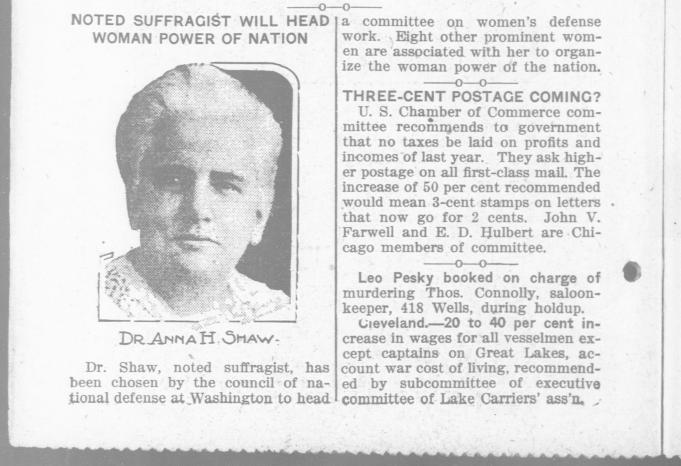

Dr. Anna H. Shaw, Suffragist (1847-1919)

Some Ninety-six years ago, 28th April 1917, the following information was found in The Day Book Dr. Anna H. Shaw, a noted suffragist, would be chosen to head the woman power of nation.

Dr. Anna H. Shaw had been chosen by the council of national defense at Washington to head a committee on women's defense work. Eight other prominent women were associated with her to organize the woman power of the nation.

According to the New York Times, dated 3 July 1919, Dr. Anna H. Shaw's obituary was as follows:

Obituary

PHILADELPHIA, July 2.--Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, honorary President of the National American Woman's Suffrage Association, died at her home in Moylan, Penn., near here, at 7 o'clock this evening. She was 72 years old.

Dr. Shaw also was Chairman of the Woman's Committee of the Council of National Defense and recently was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her work during the war.

She was taken ill in Springfield, Illinois, about a month ago while on a lecture tour with former President Taft and President Lowell of Harvard University, in the interest of the League of Nations. Pneumonia developed and for two weeks she was confined to her room in a Springfield hospital. She returned to her home about the middle of June and apparently had entirely recovered. Last Saturday she drove to Philadelphia in her automobile, and upon her return said she was feeling "fine." She was taken suddenly ill again yesterday with a recurrence of the disease and grew rapidly worse until the end.

Her secretary, Miss Lucy E. Anthony, a niece of Susan B. Anthony, who has been with Dr. Shaw for thirty years, and two nieces, the Misses Lulu and Grace Greene, were at her bedside when she died.

Dr. Shaw continued her active participation in public affairs to the last. Immediately preceding the great war, in the early Summer of 1914, Dr. Shaw went to Rome as Chairman of the Committee on Suffrage and Right of Citizenship at the quinquennial season of the International Council of Women.

Immediately after hostilities had been terminated in France by the armistice Dr. Shaw signed the resolution she helped draft for the National American Woman Suffrage Association, addressed to the Peace Conference, asking for punishment of the Germans for their crimes against women and girls.

For her endeavors in the interest of women at home as well as soldiers in France during the war, Dr. Shaw received letters from Queen Mary of England, Mme. Poincare, wife of the President of France; President Wilson, General Pershing, and other celebrities.

Dr. Shaw's Long Life of Service

In the death of the Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw there was brought to a close a life crowded with activities from her earliest youth until her last illness, a career as remarkable as it was rare. The whole course of her life was bent upon human betterment, and she was for many years a leader, especially in the cause of woman suffrage.

Dr. Shaw was born at Newcastle-on-Tyne, Eng., Feb. 14, 1847, and came to America with her parents in 1853, being nearly shipwrecked on the way over. When she was 9 years old her parents went from Massachusetts to Michigan, settling in what was then a wilderness, 40 miles from a post office and 100 miles from a railroad. In "The Story of a Pioneer," which Dr. Shaw published in 1915, she told the interesting story of her life. The family endured many hardships in that sparsely populated region. The little log cabin which they occupied had the earth for a floor, and holes in the walls instead of windows and doors. Her father was without horses or other farm animals, and without farming implements. Dr. Shaw helped plant corn and potatoes by chopping a hole in the ground with an axe. She did most of the work in the digging of a well, chopped wood for the big fireplace, felled trees, and later helped in the laying of a floor in the house and putting in doors and windows and partitions. The father was compelled to leave his wife and children at the mercy of Indians and wild animals while he earned a living for them.

When she was 15 she began teaching school, receiving $4 a week and walking eight miles a day. Later she went to live with a married sister in a Northern town. She was determined to have a college education, and by preaching and lecturing, which was frowned upon by members of her family and friends, she managed to pay her way through Albion College, where she studied from 1872 to 1875. She had only $18 in her pocket when she arrived at Albion. She later went to the Theological School of Boston University, where she was graduated in 1878. She suffered extreme poverty during this period, living in an attic in Boston. She often went cold and hungry and knew the exhaustion due to continued insufficient food and hard work.

On account of her sex, she was refused when applying for ordination by the New England Conference and by the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, but in the same year had the honor of being the first woman ordained by the Methodist Protestant Church. In her struggles to become a minister she fought against ridicule, dissension, and lack of the barest necessities.

Pioneer Among Women in the Ministry

She received a local preacher's license from the District Conference and in 1878 was pastor of the Methodist Episcopal Church at Hingham, Mass., and from 1878 to 1885 she was pastor at East Dennis, Mass. She was ordained by the Methodist Protestant Church on Oct. 12, 1880. While serving as pastor of the Dennis congregation Dr. Shaw studied medicine also at Boston University, graduating with the M. D. degree in 1885. Kansas City University conferred on her the honorary degree of D. D. in 1902 and the LL.D. degree in 1917.

When the suffrage movement began to show increasing energy in 1885, Dr. Shaw resigned her pastorate to devote her life to a fight for temperance, suffrage, and social purity. She became the lecturer for the Massachusetts Woman's Suffrage Association, and from 1886 to 1892 she was national superintendent of franchise of the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Her association through her preaching with such prominent women as Mary A. Livermore and Julia Ward Howe enlarged her view of life and aroused her enthusiasm for the causes of suffrage and liberty.

On the resignation of Dr. Shaw's most intimate friend, Susan B. Anthony, in 1900, the Presidency of the National Woman's Suffrage Association rested between Dr. Shaw and Mrs. Carrie B. Chapman, whom Miss Anthony finally chose as being the more experienced, while Dr. Shaw was made Vice President-at-Large. She had been national lecturer for the organization since 1886 and continued in this work until 1904, when Mrs. Chapman Catt was compelled to resign the Presidency on account of ill health, and Dr. Shaw succeeded her as head of the National Association. She served in this capacity until 1915, when she declined re-election.

Her administration was marked by unprecedented progress. The number of suffrage workers increased from 17,000 to 200,000, and one campaign in ten years was replaced by ten in one year; the expenditures of the association increased from $15,000 to $50,000 annually, while the number of States with full suffrage grew from four to twelve, and the whole suffrage movement changed from an academic discussion to a vital political force arousing the attention of the entire nation.

The year of 1912 was the banner year for Dr. Shaw and the cause, when Arizona, Kansas, and Oregon received full suffrage. During that year Dr. Shaw spoke in the principal cities in each of these States, making four or five speeches a day and traveling in any sort of conveyance, from freight cars to automobiles.

Dr. Shaw had spoken in every State in the Union, before many State Legislatures, and before committees of both houses of Congress. She is said to have been the only woman who ever preached in Gustav Vasa Cathedral, the State Church of Sweden, and the first ordained woman to preach in Berlin, Copenhagen, Christiania, Amsterdam, and London. In London Dr. Shaw visited all the suffrage headquarters, studying the methods and organization that prevailed there. On her return she said that she learned much, but that as to methods, the American suffrage advocates would have to work out their own. Dr. Shaw figured in a number of lively meetings of the antis, who were heckled by the suffrage advocates.

Earned Service Cross in the War

As Chairman of the Committee of Women's Defense Work, appointed by the Council of National Defense, in April, 1917, Dr. Shaw performed great services throughout the war. The Government recently awarded the Distinguished Service Medal to her for her work in this capacity, the presentation being made by Secretary of War Baker in his office at the War Department on May 12 last. During the war she wrote articles and delivered addresses in arousing the people of the country to a realization of the true meaning of the struggle with Germany.

She was greatly pleased when word came that the League of Nations offices would be open to women as well as men. She was attending the annual convention of the National Association at the time.

"It is splendid," she said. "People of the United States will understand what democracy means by the time the Peace Conference gets through and recognizes the services of women--not only recognizes their services, but their intellectual counsel and experience. The world moves. The United States must hurry."

On Dec. 15 last Dr. Shaw was sworn in as a special member of the Washington police force, having remarked at a reception the night before on the fact that she had had a forty years' desire to serve as a policewoman. The regulation oath was administered by Superintendent Pullman and Dr. Shaw received a badge.

As a minister, Dr. Shaw would not perform a marriage ceremony in which it was insisted that the word "obey" be used.

"The marriage service," she said, "is a poll-parrot affair. The method used in reciting the pledge is ridiculous, to say the least. There is no solemnity, dignity or character to that kind of marriage ceremony."

She had said that she believed in making the ceremony fit the occasion, having a different service for each marriage. As evidence of the fact that her position was right, she pointed out that she had never known of a divorce among persons married by her.

One of Shaw's last appearances in New York City was at the National Conference on Lynching, held at Carnegie Hall early in May. She was one of the leaders in arranging for the conference, and in her address she urged the passage of the Suffrage Amendment as a solution of the lynching problem. She said that women of intelligence had been brought to a realization of the fact that womanhood was not being protected by the lynching of negroes, a pretext which she described as "merely camouflage on the part of men for exhibitions of barbarism."

Though an ardent suffragist, Dr. Shaw did not approve of the methods of the militant suffrage workers. She condemned the picketing of the White House when the President was being annoyed in November, 1917, saying that the pickets had endangered the life of the President by their actions, and asserting that the pickets at the time of the visit of the Russian Mission to Washington had carried treasonable banners. Her remarks were made at the annual meeting of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association, and a resolution condemning "the mistaken methods of the pickets" was almost unanimously adopted.

In 1913 Dr. Shaw figured in a lively skirmish with the authorities in Delaware County, Penn., where she lived. Dr. Shaw refused to make out a statement of her "personal property, mortgages, stocks," and other property, returning the blank that had been left at her home to be filled out on the ground that taxation without representation was tyranny.

The Tax Assessor assessed her property at $30,000, which she declared was excessive, but the Tax Commissioner declined to do anything about the matter unless Dr. Shaw personally made out the declaration. The result was that her automobile, a pale yellow roadster, given to her by admiring suffrage workers, was levied upon and sold by the Sheriff for the taxes. The car was bought in by her friends and returned to her.

Alighting from a Lehigh Valley train in the Jersey City Station one morning in February, in 1914, Dr. Shaw slipped on the icy car step and fractured her right ankle, which laid her up for some time right in the midst of a busy speaking tour in behalf of equal suffrage. She afterward brought suit for $25,000 against the railroad company, but lost the case.

Dr. Shaw never married. She was a member of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, the League to Enforce Peace, National Society for Broader Education, the Women's Civic Club of New York, and editor of the Woman's Committee War Department of The Ladies' Home Journal. Besides writing "The Story of a Pioneer," she had contributed many short stories and articles to various magazines.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments)

| Receive

updates ( subscribers) |

Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |