|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 15 , Issue 22013Weekly eZine: (374 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

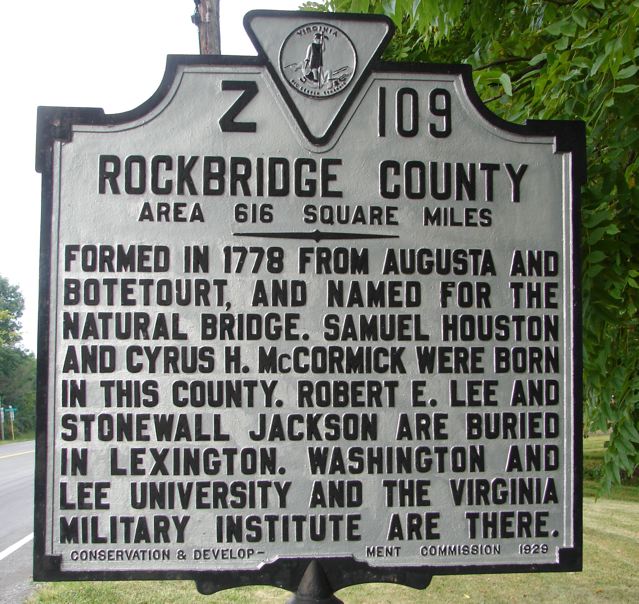

History of Rockbridge County, Virginia - Middle Period (1783-1861)

In chapter XII of Oren F. Morton's book, History of Rockbridge County, Virginia, we discover the "middle period," those years beginning with the peace of 1783 and continuing until the outbreak of another American war in 1861. It was a period that lies between two great wars.

The Middle period was that of a slow and partial unfolding. labor-saving machinery was virtually unknown when the earlier period opened and was little more than a novelty when it closed. Men wore homespun in 1780, and were still wearing ti in 1860. Men were still shooting with flintlocks in 1860. There was no change in agriculture, aside from the discontinuance of hemp about 1825. The Middle period was well under way when canal navigation entered Rockbridge, and was almost at its close when a railroad crossed the northwest corner. It was almost at its close before people began to use envelopes and stamps in mailing their letters. Brick manor-houses, very rare at the close of the War for Independence, multiplied in the more fertile neighborhoods. But throughout the eight decades the log house was the typical home in Rockbridge. The impress of the pioneer days was much in evidence even as late as 1860.

In 1775-1781, few of the men of Rockbridge county went to war except for two or three months at a time, and as no invading host came to burn academies and plunder smokehouses, the work of the farm could not have suffered in anything like the same degree as in 1861-1865. In each instance there was a depreciated paper money, a chaos of values, and commerce was almost on a vacation.

Joh Greenlee became sheriff in 1785 he found the taxes for the two preceding years uncollected, although he people were permitted to pay them in hemp at the rate of $5 per hundredweight, delivery to be made at designated places at any time before December 20, 1785. Collecting the tax Greenlee used a number of hemp receipts which the treasurer of the State was unwilling to receive. Six years later a petition to the Assembly mentioned tobacco, hemp and flour as the chief things available for paying taxes and buying necessaries. It goes on to say that the roads were rough and bad, and the price of tobacco so low that the farmers would have to abandon the crop unless it could be inspected nearer than Tidewater. The petition asked that inspection might be made at Nicholas Davis's below Balcony Falls.

The closing decades of the eighteenth century were a time of fermentation in America. Religion and mental improvement were much neglected, and there seems to have been more coarseness in word and action than in the pioneer epoch. Matters political kept in the lime light and promoted the noisy assertiveness that sprang from American independence.

The disestablishment of the Church of England was one of the first reforms of the Revolution. One half of the Virginians of 1775 were dissenters or in sympathy with the dissenters,and they could no longer be made to support a state church in addition tot he church of their choice. No taxes were paid tot he Establishment after New Year's Day, 1777. In 1802 the parish farms were ordered to be sold. yet the clerical party fought to the last ditch, and full religious liberty was not secured until 1785. The conservatives argued that conduct was governed largely by opinion, and that it was proper for the legislature to enact measures calculated to promote opinion of a desirable sort. In 1783 they urged that in place of the old Establishment each citizen should be assessed for the support of some church, in order that public morality might be maintained. The counties west of the Blue Ridge were a unit against any such half loaf. As compared with Tuckahoe Virginia they were new, poor, and radical.

To the people of Rockbridge, the war of 1812 and the war with Mexico were much less serious than the Revolution, and the casualties in battle were exceedingly few. yet in 1814 there was much illness and a number of deaths among the soldiers front he mountain counties. They were stationed not he coast, especially around Norfolk. To them the climate seemed hot and sultry, and the drinking water inferior to that of the mountain springs.

It was about 1822 there was a strong agitation for the removal of the capital to Staunton. The Assembly was bombarded with many petitions to this effect from the counties of the Western District. The movement was one of the symptoms of the discord between the two sections of the state. The feud led to the Staunton Convention of 1816 and its demand for reform in the state government. The Constitutional convention of 1829 was dominated by the reactionary element, and there was little relief until the Constitution of 1851 became law.

Until 1789 there was no mail schedule south of Alexandria. No envelopes were used with letters. The rate of postage was governed by the distance, and for a long while payment was made by the person to whom the letter was addressed. 3-cent postage did not come until 1855.

Until 1792 values were often computed in terms of tobacco, 100 pounds of the weed being equivalent to one pound in Virginia currency. In the 1830's, and onward until the war of 1861, the country was flooded banknote currency, much of it of the "wildcat" variety. The national banking system was still a thing of the future, and the man traveling from his own state into another had to exchange his home paper money for that of the other state, and undergo a "shave" in doing so. He had also to be on his guard against counterfeit bills.

The goods for the merchants of Lexington came by the Tennessee road wagon, a huge vehicle drawn by six horses in gay trappings. The cover was sometimes of bearskin instead of canvas. The wagoner was somewhat like the boatman of the Western rivers. He was a hardy, swaggering personage, but the state driver would not tolerate the idea of lodging int he same tavern with him.

The polling places in 1830 were four" Joseph Bell's at Goshen, H. B. Jones' at Brownsburg, the tavern at Natural Bridge, and the house of one of the numerous Moores. Four years later, the tavern of John McCorkle became a voting place, and in 1845 the tavern of John Albright at Fairfield.

Outside of the county seat and the few villages, Rockbridge had in 1835 there furnaces, six forges, ten stores, and twenty-four gristmills. Of the thirteen country churches, nine were Presbyterian.

Before the Revolution, the gentleman appeared on state occasions in a dress suit of broadcloth, often dark blue, but sometimes plum or pea green. His long waistcoat was black and his trousers of some light color. His tall black hat was similar to the "stove-pipe" of a later day. At the top of his ruffled short-bosom appeared a tall, stiff collar of the type known as a stock, and around this was fastened a black silk handkerchief. His hair was cropped short to make room for a powdered wig. Women wore towering bonnets. The long-necked dress had a cape or collar and enormous mutton-leg sleeves. By the close of the war of 1812, tight breeches had just gone out of fashion. The coat was "high int he collar, tight int he sleeve, short int he back, and swallow-tailed. The hat was narrow-brimmed and bell-crowned."

The cravat was a white handkerchief, stiff-starched and voluminous, the flowing ends resting on a ruffled shirt-bosom. The pocket handkerchief was a bandanna. Gloves were not much worn. Woman's dress was "plain in color, short in waist, narrow in skirt. As soon as a woman was married she put on a cap." Imported goods were not in general use, but were worn year after year.

In the country, grandchildren could see the wedding coat still on granddaddy's back on state occasions. In the 1850's a certain citizen of Rockbridge county was wearing linen trousers forty years old, yet seemingly as good as new. A few moccasins were still worn. Work-shoes were of cowhide, dress shoes of calfskin. The farmer's boy had to make one pair last a year.

In 1810 not less than 5,000,000 yards of homespun linen were manufactured in Virginia, and much the greater share of this output originated west of the Blue Ridge. Until about the middle of the century it was only the people of aristocratic tastes who wore clothing made of imported cloth. The hemp that was not sent to market was made into sacking, or into a hard, strong cloth of a greenish hue that slowly turned to a white.

The flax patch was seldom of more than one acre. The stalks were pulled when the seeds were fully ripe, and were laid out in gavels, the stem-ends forming a line. After a while the bundles were set up, and then dry were put into the barn. In the winter season the stalks were broken to loosen the fiber. This was done by laying them against slats and giving a few blows with a wooden knife. Scutching was the next step, and was performed by holding the broken stems against an upright board and striking them obliquely with the same knife. Then came in succession the spinning, the weaving, and the bleaching. The unbleached cloth was of the color of Flaxen hair. The homemade linen was of two grades, one for fine and one for coarse cloth. Six yards a day was about the utmost the weaver could accomplish, if the weaving were to be tight enough.

The log house of "ye olden time" had a floor of pine or poplar puncheons, made smooth and level with the adze. As spaces appeared int he process of drying, the puncheons were moved closer together. The building of the roof had taken its place among the lost arts. The first gable-log projected one foot at each end, and was held in place by strong locust pins. The upper gable-logs, or eave-bearers, were held by the rest-poles on which the clapboards were laid. Stretching between the first gable-logs was the eave-pole, which held the first course of clapboards. Rest-poles were laid between the upper gable-logs.

The clapboards were three feet long and eight inches wide, and were laid with twelve inches of lap. Each course was held down by what was sometimes called a weight-pole and sometimes a press-pole. This fitted at each end into a notch in the gable-log and was further secured by a peg. Between each weight -pole and the one above it was a support called a knee. The uppermost weight-pole was heavier than the others and was pinned to its position. A rustic way of securing the top courses was with a pair of split poles, one of the halves lying against one side of the crown and one against the other. The ends were tied together with grapevine or hickory withes. When the pins in a press-pole rotted, the poe with its course of clapboards would slide to the ground. The chimney was of short logs well daubed inside with clay. Near the fireplace was the opening called the light-hole. When not inure it was covered with a sliding board. One lazy man broke a hole in the bad of his chimney, so that he could poke his firewood through it instead of bringing it in by the door.

The doghouses of the larger and better class had chimneys of stone, sometimes containing an enormous amount of masonry. In this county the stone house generally appeared earlier than the one of brick, and was sometimes intended to answer the purpose of a defense against the Indians. Limestone was abundant in Rockbridge, but had been little used in house-walls. Colonel John Jordan, a native of Hanover county and a builder of many brick mansions and other structures, was said to have introduced the colonial style of architecture into Rockbridge.

Corn pone was much in use, and the other ordinary forms of the staff of life were spoon bread, batter bread, and sponge bread. Stoves began to come into use about 1850, and at first were not well thought of. The loom-house was an adjunct of the preparing farm. Elsewhere, the loom was a feature of the living-room or the kitchen. girls who learned to weave were able to make some money by going from house to house.

The country store was a very plain affair and was destitute of showcases. Only the most common goods and necessaries were on exhibit. The business of the store seemed to move at a slow pace, yet the merchant was prosperous. After the war of 1816 there was a more rapid gait.

Did you know there were two types of garden: one with beds and herbs and one without. Because of the climate of Scotland was not quite favorable to the kitchen garden, which was not generally adopted by the Scotch-Irish settlers of the Valley of Virginia until they took a hint by seeing the gardens put out by the Hession prisoners of war at Staunton. The herbs were sage, ditty, boneset, catnip, horsemint, horehound, old man, and old woman. These were used as home remedies, especially by the granny woman, who in no small degree stood in the place of the doctor. She used lobelia as an emetic, white walnut bark as a purgative, snakeroot for coughs, and elder blossom to produce perspiration. The bark of dogwood, cherry, and poplar, steeped in whiskey, was used for fever and ague. For the much dreaded dysentery, she employed Mayapple root, walnut bark, and slippery elm bark. A favorite way of treating a cold was for the patient to warm his feet thoroughly before a fire and then cover up in bed.

Petticrew (Pettigrew) Tragedy of 1846 In Rockbridge

it was the most distressing tragedy in the history of Rockbridge that took place in the earlier half of the night of December 16 & 17, 1846. John Petticrew, a native of Campbell county, fell into straitened circumstances , and in 1843 moved into a log house in the southward facing cove between the two house mountains. The wife of Petticrew had been Mary A. Moore, of Kerr's Creek. The oldest of the six children was sixteen, the youngest was six, and all were healthy and strong. The evening of December 16th was snowy, and by midnight there was high wind. Next morning the snow was much drifted, and for several days the weather was very cold. The fourth day was Sunday, and in the morning Mr. Petticrew (Pettigrew) came home according to his custom from his work at the distillery of William Alphin. To his horror he found his house burned tot he ground. Lying near by were the frozen and partially clad bodies of the wife and all the children except the oldest, a daughter who was with her sick grandmother on Kerr's Creek. Strong men wept when they saw the corpses laid out for burial. Foul play was suspected on the part of James Anderson and his wife Mary, who lived a half mile away. The Andersons did not beat a good name. The husband was not one of the crowd that gathered on the Sunday that Petticrew made his grew some discovery, nor was he present at the burial. Petticrew had had some trouble wight he neighbor because of Anderson's cows breaking into his field. He was knocked down by Anderson, who tried to choke him. Armed with a search warrant, a brother to mrs. Petticrew visited the Anderson home and found therein a coverlet and some other articles that had belonged to her. The silverware of the Petticrews was not found. Anderson was tired in Bath, but was acquitted on the ground of insufficient evidence. He went to Craig and never again lived in Rockbridge. It remained the common opinion that Anderson was really guilty, and there was a story that in a fit of remorse he made a deathbed confession.

And yet an examination of the corpses was inconclusive as tot whether death came from violence or from the intense cold following a fire either accidental or intentional. Within tow years Petticrew died of a broken heart. The daughter who was away from home subsequently married James G. Reynolds and had two children. The victims of the tragedy were buried at Oxford. The stone over the grave was shattered by lightning and was replaced with a monument paid for by friends of the family.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments)

| Receive

updates ( subscribers) |

Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |