|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 17 , Issue 202015Weekly eZine: (366 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

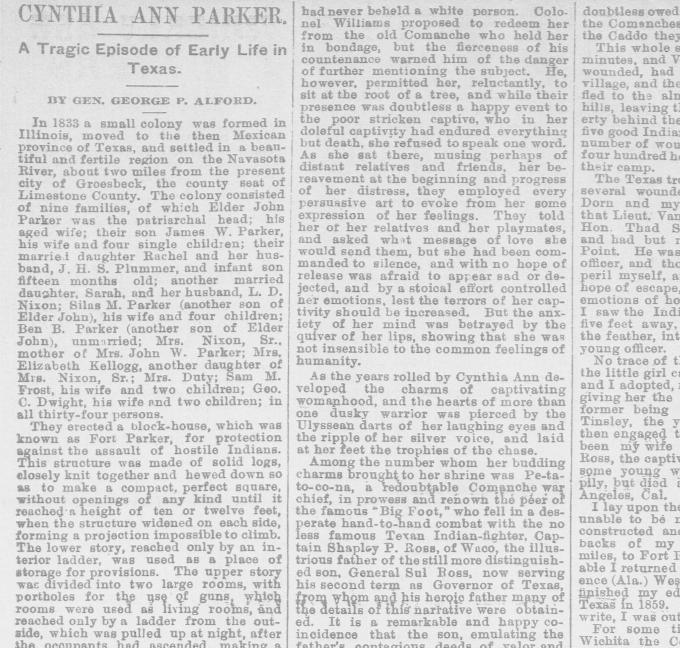

A Tragic Episode of Early Life In Texas, Cynthia Anne Parker - by Gen. George P. Alford, 1890

The Phillipsburg Herald, out of Phillipsburg, Kansas, dated 18 September 1890, page 6, had the following story of "Cynthia Ann Parker - A Tragic Episode of Early Life In Texas," as written by Gen. George P. Alford.

In 1833 a small colony was formed in Illinois, moved to the then Mexican province of Texas, and settled in a beautiful and fertile region on the Navasota River, about two miles from the present city of Grosbeak, the county seat of Limestone county.

The colony consisted of nine families, of which Elder John Parker was the patriarchal head; his aged wife; their son James W. Parker, his wife and four single children; their married daughter Rachel and her husband, J. H. S. Plummer, and infant son fifteen months old; another married daughter, Sarah, and her husband, L. D. Nixon; Silas M. Parker (another son of Elder John), his wife and four children; Ben B. Parker (another son of Elder John), his wife and four children; Ben B. Parker (another son of Elder John), unmarried; Mrs. Nixon, Sr., mother of Mrs. John W. Parker; Mrs. Elizabeth Kellogg, another daughter of Mrs. Nixon, Sr.; Mrs. Duty; Sam M. Frost, his wife and two children; Geo C. Dwight, his wife and two children; in all thirty-four persons.

they erected a block-house, which was known as Fort Parker, for protection against the assault of hostile Indians. This structure was made of solid logs, closely knit together and hewed down so as to make a compact, perfect square, without openings of any kind until it reached a height of ten or twelve feet, when the structure widened on each side, forming a projection impossible to climb. The lower story, reached only by an interior ladder, was used as a place of storage for provisions. The upper story was divided into two large rooms, with portholes for the use of guns, which rooms were used as living rooms, and reached only by a ladder from the outside, which was pulled up at night, after the occupants had ascended, making a safe fortification against a reasonable force, unless assailed by fire. These hardy sons of toil tilled their adjacent fields by day, always taking their arms with them, and retired to the fort at night. Success crowned their labors, and they were prosperous and happy.

On the morning of May 18, 1836, the men, unconscious of impending danger, left as usual for their fields, a mile distant. Scarcely had they left the inclosure when the fort was attacked by about seven hundred Comanches and Kiowas, who were waiting in ambush. A gallant and most resolute defense was made, many savages being sent by swift bullets to their "happy hunting ground," but it was impossible to stem the terrible assault, and Fort Parker fell. Then began the carnival of death. Elder John Parker, Silas M. Parker, Ben F. Parker, Sam M. Frost and Robert Frost were killed and scalped in the presence of their horror-stricken families. Mrs. John Parker, Granny Parker and Mrs. Duty were dangerously wounded and left for dead, and the following were carried into a captivity worse than death. Mrs. Rachel Plummer, Jas. Pratt Plummer, her two year old son; Mrs. Elizabeth Kellogg, Cynthia Ann Parker, nine years old, and her little brother John, aged six; both children of Silas M. Parker.

The remainder of the colony made their escape, and after incredible suffering, being forced even to the dire necessity of eating skunks to save their lives, they reached Fort Houston, now the residence of Judge John H. Reagan, united states Senator, about three miles from the present city of Palestine, in Anderson county, where they obtained prompt succor, and a relief party buried their dead.

We will now attempt briefly, to follow the fortunes of the poor captives. The first night after the massacre the savages camped on an open prairie, near a water hole, staked their horses, pitched their camp and threw out their videttes. Then they brought out their prisoners and stripped them and tied their hands behind them, and their feet closely together with rawhide thongs, so tightly as to cut the flesh, threw them upon their faces and the braves gathering around with the yet bloody dripping scalps of their martyred kindred, began their usual war dance, alternately dancing, screaming, yelling, stamping upon their helpless victims, beating their naked bodies with bows and arrows until the flowing blood almost strangled them. These orgies continued at intervals through the terrible night, which seemed to have no end, these frail women suffering and compelled to listen to the cry of their tender little children.

Mrs. Kellogg, more fortunate than the others, soon fell into the hands of the Kecchi Indians, who, six months later sold her to the Delawares, who carried her to Nacogdoches, where this writer then lived, a small child with his parents. Here she was ransomed for $150 by General Sam Houston, who promptly restored her to her kindred.

Mrs. Rachel Plummer remained a captive for eighteen months, suffering untold agonies and indignities, when she was ransomed by a Santa Fe Trader named William Donahue, who soon after escorted her to Independence, Mo., from whence she finally made her way back to Texas, arriving Feb. 19, 1838. Her son, James Pratt Plummer, after remaining a prisoner six years, was ransomed at Fort Gibson, and reached his home in Texas in February, 1843, then aged 8 years.

During Mrs. Plummer's captivity she again became a mother. When her child was 6 months old, finding it an impediment to the menial labors imposed upon her as a slave, a Comanche warrior forcibly took it from her arms, tied a lariat around its body, and mounting his horse, dragged the infant at full speed around the camp in sight of the agonized mother until life was extinct, when its mangled remains were tossed back into her lap with savage demonstrations of delight. Such atrocities have forced me to the belief that "all good Indians are dead Indians."

This leaves of the sorrowing captives only Cynthia Ann parker and her little brother John, 6 years of age, each held by separate bands. John grew up to athletic young manhood, married a beautiful night-eyed young Mexican captive, Donna Juanita Espinosa, escaped from the savages, or was released by them, joined the Confederate army under Gen. H. P. Bee, became noted for his gallantry and daring, and at latest accounts was leading a happy, contented pastoral life as a ranchero on the Western Llano Estacado of Texas.

Cynthia Ann Parker

Four long and anxious years have passed since Cynthia Ann Parker was taken from her weeping mother's arms, during which no tidings had been received from her anxious family, when, in 1840, Col. Len Williams, an old and honored Texan, Mr. Stout, a trader, and Jack Harry, a Delaware Indian guide, packed mules with goods and engaged in an expedition of private traffic with the Indians. On the Canadian River they fell in with Pahuaka's band of Comanches, with whom they were peaceably conversant.

Cynthia Ann Parker was with this tribe, and from the day of her capture had never beheld a white person. Colonel Williams propose dot redeem her from the old Comanche who held her in bondage, but the fierceness of his countenance warned him of the danger of further mentioning the subject. He, however, permitted her, reluctantly, to sit at the root of a tree, and while their presence was doubtless a a happy event to the poor stricken captive, who in her doleful captivity had endured everything but death, she refused to speak one word. As she sat there, musing perhaps of distant relatives and friends, her bereavement at the beginning and progress of her distress, they employed every persuasive art to evoke from her some expression of her feelings. They told her of her relatives and her playmates, and asked what message of love she would send them, but she had been commanded to silence, and with no hope of release was afraid to appear sad or dejected, and by a stoical effort controlled her emotions, lest the terrors of her captivity should be increased. But the anxiety of her mind was betrayed by the quiver of her lips, showing that she was not insensible to the common feelings of humanity.

As the years rolled by Cynthia Ann developed the charms of captivating womanhood, and the hearts of more than one dusky warrior was pierced by the Ulysses darts of her laughing eyes and the ripple of her silver voice, and laid at her feet the trophies of the chase.

Among the number whomever budding charms brought to her shrine was Pe-ta-to-co[na, a redoubtable Comanche war chief, in prowess and renown the peer of the famous "Big Foot," who fell in a desperate hand-to-hand combat with then less famous Texan Indian-fighter, Captian Shapley P. Ross, of Waco, the illustrious father of the still more distinguished son, General Sul Ross, now serving his second term as Governor of Texas, from whom and his heroic father many of the details of this narrative were obtained. It is a remarkable and happy coincidence that the son, emulating the father's contagious deeds of valor and prowess, afterward in single combat in the valley of the Wichita, forever put to rest the brave and knightly Pe-ta-no-co-na.

Cynthia Ann, stranger now to every word of her mother tongue, save only her childhood name, became the bride of the brown warrior Pe-ta-no-co-na, bore him three children, and loved him with fierce passion and wifely devotion, evidenced by the fact that fifteen years after her capture a party of hunters, including friends of her family, visited the Comanche encampment on the Upper Canadian River, and recognizing Cynthia Ann through he medium of her name, endeavored to induce her to return to her kindred and the abode of civilization. She shook her head in a sorrowful negative, and, pointing to her little naked barbarians sporting at her feet and to the great lazy chief sleeping in the shade near by, the locks of a score of fresh scalps dangling at his belt, replied:

"I am happily wedded; I love my husband and my little ones, who are his, too, and I cannot forsake them."

Recapture of Cynthia Ann Parker Pe-ta-no-co-na

This brilliant achievement and the thrilling events which preceded it, can best be told in the graphic language of the hero who accomplished it, General Lawrence Sullivan Ross, Governor of Texas, and I therefore append his modest letter:

- Executive Office, Austin, Texas, April 8, 1890. Gen. Geo. F. Alford, Dallas, Texas:

My Dear General: In response to your request. I herewith inclose you my recollections, after a lapse of thirty years, of the events to which you refer:

In 1858, Major Earle Van Dorn, with the Second Cavalry, U. S. A., one company of infantry to guard his depot of supplies,and 15 friendly Indians under my command, made a successful campaign against the Comanches, and by a series of well directed blows,inflected terrible punishment upon them. On the morning of October 1, 1858, we came in sight of a large Indian village on the waters of the Wichita River near what is now known as Fort Sill, in the Indian Territory. They were not apprehensive of an attack and most of them were still asleep. Major Van Dorn directed me, at the head of my Indians, to charge down the line of their lodges or tents, cut off their horses and run them back on the hill. This was quickly accomplished. Van Dorn then charged the village, stikit at the upper end, as it stretched along a boggy branch. After placing about thirty-five of my Indians as a guard around the Comanche horses, some 400 in number, I charged with the balance of my Indian force into the lower end of the village.

The morning was very foggy and after a few minutes of firing the smoke and fog became so dense that objects at but a short distance could be distinguished only with great difficulty. The Comanches fought with great desperation, as all they possessed was in imminent peril. Shortly after the engagement became general, I discovered a number of Comanches running down the branch, about 150 years from the village, and concluded they were retreating. About this time I was joined by Lieutenant Van Camp, U. S. A., and a regular soldier by the name of Alexander. With these and one Caddo Indian i ran to intercept them, thus becoming separated from he balance of my force. I soon discovered that the fugitives were women and children. Just then, however, another posse of them came along,a nd as they passed I discovered in their midst a little white girl, and made the Caddo Indian seize her as she was passing. She was about eight years of age and became badly frightened and difficult to among when she found herself detained by us. I then discovered, much to my dismay, that about twenty-five Comanche warriors, under cover of the smoke, had cut off my small party of four from communication with our comrades and were bearing down upon. They shot Lieut. Van Camp through eh heart, killing him while he was in the act of firing his double[barreled gun. Alexander was next shot down and his rifle tell out of his hands. I had a Sharp's rifle, and attempted to shoot the Indian just as he shot Alexander, but the cap snapped. Another warrior named Mohee, whom I had often seen at my father's camp on the frontier, when he was Indian Agent, then seized Alexander's loaded gun and shot me through the body. I fell upon the side on which my pistol was borne, and, though partially paralyzed by the shot, I was endeavoring to turn myself and get my revolver out, when the Comanche nearest me drew out a long bladed butcher knife and started to stab and scalp me. It seemed that my time had certainly come. He made but a few steps, however, when one of his companions cried out something in the Comanche tongue, and they all broke away and fled in confusion. Moree, the Indian who shot me, ran only about twenty steps when he received a load of buckshot fired from a gun in the hands of Lieut. James Majors, of the Second Cavalry, U.S. A., who with a party of solders had opportunely come to my rescue.

During this desperate melee the Caddo held on to the little white girl, and doubtless owed his escape to that fact, as the Comanches were afraid if they shot the Caddo they would kill the little girl.

This whole scene transpired in a few minutes, and Van Dorn, although badly wounded, had possession of their entire village, and the surviving Comanches had fled to the almost impenetrable bushy hills, leaving their dead and their property behind them, consisting of ninety-five good Indians (being dead Indians), a number of wounded and captives, about four hundred horses, and all the spoils of their camp.

The Texas troops had five killed and several wounded, including Major Van Dorn and myself. My recollection is that Lieut. Van Camp was a protege of Hon. Thad Stevens, of Pennsylvania, and had but recently come from West Point. He was a gallant and chivalrous officer, and though at the time in deadly peril myself, and entirely bereft of all hope of escape, I shall never forget the emotions of horror that seized me when I saw the Indian warrior, standing not five feet away, send his arrow, clear to the feather, into the heart of that noble young officer.

No trace of the parentage or kindred of the little girl captive could ever be found, and I adopted, reared, and educated her, giving her the name of Lizzie Ross, the former being in honor of Miss Lizzie Tinsley, the young lady to whom I was then engaged to be married, and who has been my wife since May, 1861. lizzie Ross, the captive girl, free into a handsome young woman, and married happily, but died a few years ice at Los Angeles, Cal. I lay upon the battle field for five days, unable to be moved, when a litter was constructed and I was carrie don the backs of my faithful Caddis ninety miles, to Fort Radziminski. As soon as able I returned to my alma mater, Florence (Ala.) Wesleyan University, where I finished my education, and returned to Texas in 1859. At the period of which I write, I was out on vacation.

For some time after the battle of Wichita the Comanches were less troublesome to the people of the Texas frontier, but in 1859 and 1860 the condition of the frontier was again truly deplorable. The loud and clamorous demands of the settlers induced the State Government to send out a regiment under Col. M. T. Johnson for public defense. The expedition, though of great expense to the sTate, failed to accomplish anything. Having just graduated and returned to my home at Waco, I was commissioned as Captain by Gov. Sam Houston, and directed to organize a company of sixty men, with orders to repair to Fort Belknap, in Young county, receive from Col. Johnson all Government property, as his regiment was disbanded, and offer the frontier such protection as was possible from so small a force.

The necessity for vigorous measures soon became so pressing, however, that I determined to attempt to curb the insolence of these implacable, hereditary enemies of Texas, who were greatly emboldened by the small force left to confront them, and to accomplish this by following them into their fastnesses, and carry the war into their own homes. I was compelled, after establishing a post, to leave twenty of my men to guard the Government property,a nd give some show of protection to the frightened settlers,a nd as I could take but forty of my men I requested Capt. N. G. Evans, in command of the United States Cavalry. We had been intimately connected in the Van Dorn campaign in 1858, during which I was the recipient of much kindness from him while I was suffering from he severe wound received in the battle of the Wichita. He promptly sent me a sergeant and twenty well-mounted men, thus increasing my force to sixty. My force was still further augmented by some seven volunteer citizens, under the brave old frontiersman, Capt. Jack Cureton, of Bosque county.

On Dec. 18, 1860, while marching up Pease River, I had suspicions that Indians were in the vicinity by reason of the great number of buffalo which came running toward us from the north, and while my command moved in the low ground I visited neighboring high points to make discoveries. On one of these sand hills I found four fresh pony tracks, and being satisfied that Indian vedettes had just gone, I galloped forward about a mile to a still higher point, and riding to the top to my inexpressible surprise found myself within two hundred yards of a large Comanche village, located on a small stream, winding around the base of a hill. It was most happy circumstance that a cold, piercing wind from the north was blowing, bearing with it clouds of dust and my presence was thus unobserved and the surprise complete. By signaling my men as I stood concealed they reached me without being discovered by the Indians who were busy packing up, preparatory to move.

By the time my men reached me the Indians had mounted and moved off north across the level plain. My command, including the detachment of the Second Cavalry, had outmatched and become separated from the citizen command of seventy, which left me about sixty men. In making disposition for the attack, the sergeant and his twenty men were sent at a gallop behind a chain of sandhills to encompass them and cut off their retreat, while with my forty men I charged. The attack was so sudden that a large number were killed before they could prepare for defense. They fled precipitately right into the arms of the sergeant and his twenty men. Here they met with a warm reception, and, finding themselves completely encompassed, every one fled his own way and was hotly pursued and hard pressed. The chief, a noted warrior of great repute, name Pe-ta-no-co-na, with a young Indian girl about fifteen years of age mounted on his horse behind him, and Cynthia Ann Parker, his squaw, with a girl child about two years old in her arms and mounted on a fleet pony, fled together. Lieutenant Tom Kelliheir and I pursued them, and after running about a mile Kelliheir ran up by the side of Cynthia Ann's horse, and supposing her to be a man, was in the act of shooting her when she held up her child and stopped. I kept on alone at the tope of my horse's speed, after the chief, and about half a mile further, when within about twenty yards of him, I find my pistol striking the girl (whom I supposed to be a man, as she rode like one, and only her head was visible above the buffalo robe with which she was wrapped) near the heart, killing her instantly. And the same ball would have killed both but for the shield of the chief, which hung down covering his back.

When the girl fell from the hose dead, she pulled the chief off also, but he caught on his feet and before steadying himself my horse, running at full speed, ws nearly upon him, when he sped an arrow which struck my horse and caused him to pitch or "buck," and it was with the greatest difficulty I could keep my saddle, meantime narrowly escaping several arrows coming in quick succession from the chief's bow. Being at such disadvantage, he undoubtedly would have killed me but for a random shot from my pistol, while I was slinging with my left hand to the pommel of my saddle, which broke his right arm at the elbow, completely disabling him. My horse then becoming more quiet, I shot the chief twice through the body, whereupon he deliberately walked to a small tree near by, the only one in sight, and, leaning against it, with one arm around it for support, began to sing a wild, weird song, the death-song of the savage. There was a plaintiff melody in it which, under the dramatic circumstances, filled my heart with sorrow. At this time my Mexican servant, who had once been a captive with the Comanches and spoke their language as fluently as his mother tongue, came up in company with others of my men. Through him I summoned the chief to surrender, but he promptly treated every overture with contempt, and signalized his refusal with a savage attempt to thrust me through with his lance, which he stilled in his left hand. I could only look upon him with pity and admiration, for deplorable as was his situation, with no possible chance of escape, his army utterly destroyed, his wife and child captives in his sight, he was undaunted by the fate that awaited him, and, as he preferred death toll if, I directed the Mexican to end his misery by a charge of buckshot from the gun which he carried, and the brave savage, who had been so long the scourge and terror of the texan frontier, passed into the land of shadows and rested with his fathers.

Taking up his accouterments, which I subsequently delivered to General Sam Houston, as Governor of Texas and Commander-in-chief of her soldiery, to be deposited in the State archives at Austin, we rode back to the captive woman, whose identity was then unknown, and found Lieutenant Kellerheir, who was guarding her and her child, bitterly cursing himself for having run his pet horse so hard after an "Old squaw." She was very dirty and ar from attractive in her scanty garments, as well as her person, but as soon as I looked on her face, I said, "Why! Tom, this is a white woman; Indians do not have blue eyes."

On our way to the captured Indian village where our men were assembling with the spoils of battle and a large cavalcade of Indian ponies which we had capture, I discovered an Indian boy about nine years old secreted in the tall grass. Expecting to be killed, he began to cry, but I made him mount behind me and carried him along, taking him to my home at Waco, where he became an obedient member of my family. When, in after years, I tried to induce him to return to his people, he refused to go, and died in McLennan county about four years ago.

When camped for the night, Cynthia Ann, our then unknown captive, kept crying, and thinking it was caused from fear of death at our hands, I had the Mexican tell her, in the Comanche language, that we recognized her as one of our own people and would not harm her. She replied that two of her sons in addition tot he infant daughter were with her when the fight began, and she was distressed by the fear that they had been killed. It so happened, however, that both escaped, and one of them, Quanah, is now the chief of the Comanche tribe. The other son died some years ago on the plains. Through my Mexican interpreter I then asked her to give me the history of her life with the Indians and the circumstances attending her capture by them, which she promptly did in a very intelligent manner, and as the facts detailed by her correspond with the massacre at Parker's Fort in 1836, I was impressed with the belief that she was Cynthia Ann Parker.

Returning to my post, I sent her and her child to the ladies at Camp Cooper, where she could receive the attention her sex and situation demanded, and at the same time I dispatched a messenger to Col. Isaac Parker, her uncle, near Weatherford, Parker county, named as his memorial, for he was for many years a distinguished Senator in the Congress of the republic and in the Legislature of the State after annexation. When Col. Parker came to my post I sent the Mexican with him to camp Cooper in the capacity of interpreter, and her identity was soon discovered to Col. Parker's entire satisfaction. She has been a captive just twenty-four years and seven months, and was in her thirty-fourth year when recovered. The fruits of that important victory can never be computed in dollars and cents. The great comanche confederacy was forever broken, the blow was decisive, their illustrious chief slept with his fathers, and with him were most of his doughty warriors, many captives were taken, 450 horses, their camp equipage, accumulated winter supplies, etc.

If I could spare time from my official duties, and had patience, I could furnish you with many thrilling incidents never published relating to the early exploits, trials and sufferings of the pioneers. My father was appointed Indian Agent in 1856. He had an excellent memory and treasured these until later in life I listened by the hour to their recital. I remain, my dar General, sincerely your friend, L. S. Ross.

But little of this sad episode remains to be told. Cynthia Ann and her infant barbarian were taken to Austin, the capital of the State. The immortal Sam Houston was Governor, and the Secession Convention was in session. She was taken to the State House, where this august body were holding grave discussion as to the policy of withdrawing from he Federal compact. Cynthia Ann, comprehending not one word of her mother tongue, concluded it was a council of mighty chiefs, assembled for the trial of her life, and in great alarm tried to make her escape. her brother, Hon Dan Parker, who resided near Parker's Bluff, Anderson county, was a member of the Legislature from that county and a colleague of this writer, who then represented the Eleventh Senatorial District.

Colonel Dan Parker took his unhappy sister to his comfortable home, and essayed by the kind offices of tenderness and affection to restore her to the comforts and enjoyments of civilized life, to which she had been so long a stranger. But as thorough an Indian in manner and looks as if she had been active born, she sought every opportunity to escape and rejoin her dusky companions, and had to be constantly and closely watched.

The civil strife then being waged between the North and South, between fathers, sons and brothers, necessitated the primitive arts of spinning and weaving, in which she soon became an adept, and gradually her mother tongue came back, and with it occasional incidents of her childhood. But the ruling passion of her bosom seemed to be the maternal instinct, and she cherished the hope that when the cruel war was over she would at last succeed in reclaiming her two sons who were still with he Comanches. But the Great Spirit had written otherwise, and Cynthia Ann and little Prairie Flower were called in 1864 to the Spirit Land, and peacefully sleep side by side under the great oak trees on her brother's plantation near Palestine, Texas.

Thus ends the sad story of a woman shoe stormy life, darkened by an eternal shadow, made her famed throughout the borders of the imperial Lone Star State. When she left it, an unwilling captive, it contained scarce 50,000 people, and was distracted by foreign and domestic war. Today it contains three millions, and is the abode of refinement.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments) | Receive updates ( subscribers) | Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |