|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 15 , Issue 72013Weekly eZine: (366 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

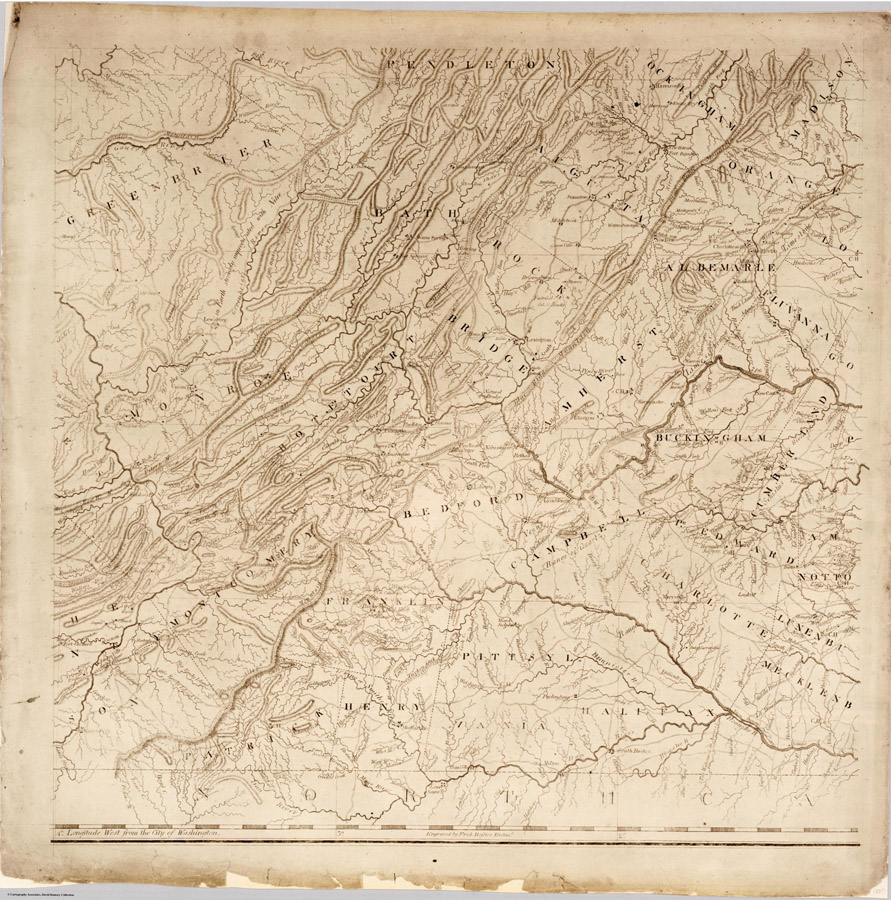

History of Rockbridge County, Virginia - The Negro Element

African slavery was almost as unfamiliar too the British people in their own land as it was in the whitest county of the Old Dominion. It was not legalized in Virginia until more than fifty years after the founding of Jamestown.

White servants were preferred to colored ones until after Negroes of American both were more satisfactory laborers than those coming direct from Africa. slavery grew in favor, and when American independence was declared, the negro population of Virginia was already so large that it seemed likely to exceed the white at an early day.

The far-seeing ruling class in Virginia perceived the undesirability of this inundation. The House of Burgesses repeatedly asked the British government to cease bringing negroes to the colony. All these efforts were set at naught by the greed of the mercantile classes of England. On the eve of the Revolution, Lord Dartmouth said England "cannot allow the colonies to check or discourage in any degree a traffic sos beneficial to the nation."

This forcing of slaves upon Virginia was one of the grievances named by Jefferson in his original draft of the Declaration of Independence. It must be conceded that slaves would not have been brought to Virginia unless there was a willingness to buy them. A stern boycott would have ended the traffic. No British ministry would have dared to break down such a weapon by sheer force.

The summer climate of Virginia was considerably warmer than that of Britain and had very little todo with the importation of slaves. Black slaves as well as white servants were purchased because the society of Tidewater was essentially aristocratic. Where there is an aristocracy, there is inevitably a menial class. The Tidewater was a land of tobacco plantations, and these could not be carried on without a large class of laborers. Above the Tidewater and below the Blue Ridge, slaves were fewer than in the former section. In the Valley they were still fewer, and in many of the counties beyond the Alleghany Divide they were almost non-existent. Slaves and large farms grew fewer and yet fewer as one journeyed toward the Ohio.

The institution of slavery was vehemently denounced by the delegates from Virginia to the Federal Convention of 1787. A Virginia law of 1784 encouraged the freeing of the slaves. In the same year the Methodists of America became an independent church, and one of their first official acts was to petition against slavery, although most of their membership was then in Virginia and Maryland. slavery tended to make manual labor discreditable unless it it was performed by slaves. It thereby degraded the lower classes of society and contributed to idleness in the higher. It was a Southern man who tersely described slavery asa "a curse to the master and a wrong tot he slave." It was another who defined it as "a mildew which has blighted eery region it has touched from the creation of the world."

Colonial Augusta was almost a white man's country. In 1756 it had only about 80 slaves; perhaps not more than one per cent of the population. But thence forward they became increasingly numerous in the better agricultural districts of the Valley. In Rockbridge they were few prior to the Revolution, and they were confined to a small number of the wealthier families. When the iron industry arose and made a demand for labor, negroes were hired from masters east of the Blue Ridge. By 1861, colonel Preston remarked, "We were quite slaveholding people; a few more hears, and we would have had to undergo much that Tuckahoe did on that score. It was well the unpleasantness came as soon as it did."

So completely have the outward vestiges of the reign of slavery passed away from Rockbridge, that only a few of the original negro quarters remain. A notable exception in the Weaver estate at Buffalo Forge, where the houses for the slaves were of an uncommonly substantial and comfortable kind. The institution was milder in Virginia than in the cotton belt, and the relations between master and slave were as a rule kindly.

Since the African came to Virginia as a child-race, and was not used to any softer argument than brute force, it was felt that slavery could not be maintained by treating the negro in the same manner as the white man. The slave was supposed not to carry a gun or to go outside his master's premises without a pass. Poisons might not be put into his hands, and this restriction was necessary. In 1839 a Rockbridge salve attempted to poison several persons. H might not be taught to read or write. But between himself and his own slaves the master did to think the law had any claim to interfere. Accordingly, if he saw fit, he taught a favorite slave to read and write.

The patrol system was one means of keeping the slaves in order, and it occasioned a good deal of expense. Captains were appointed by the county court, each having a force of some six or eight men. A captain and his squad would patrol a specified area at specified times. For this service the patrolman was paid thirty-three cents a night in 1782. The penal code was not the same to the slave that it was to the Caucasian. His ears could be cropped. He could be hanged for burning a barn, or for stealing, and the county court was empowered to decree the death penalty. Before the negro was hanged, his valuation as a slave was determined, and this sum was paid by the county o the master.

A considerable share of the crime in Rockbridge had been committed by the negro. The first civil execution of a white man in this county took place 3 August 1905. It was preceded by the legal hanging of five negroes at five different times. York, a slave of Andrew Reid, was adjudged guilty 1 december 1786, of killing Tom, another of Reid's slaves. It was ordered that he be hanged one week later, that his head be severed from the body, and that it be set on a pole at the forks of the road between Lexington and John Paxton's. Rape was not at all unknown before emancipation An execution for this crime took place in Rockbridge in 1850. For assaulting and beating Arthur McCorkle, Alexander Scott was ordered to be hanged 5 April 1844. The master was tone paid $450. Cyrus, a slave of Robert Piper, was ordered to hang in 1798 for burning his master's house. In 1840, Nelson, a slave, was ordered to be hanged for burglary. Outlaw slaves might be put to death with impunity. But the penalty for burglary was sometimes hanged to transportation to Liberia. Whipping was administered in less serious matters, as when thirty-nine lashes were ordered for Peter, a slave of John Hays, in 1800. He had stolen leather worth. In 1804, Jinny, a slave of John Dunlap, threatened his wife, Dorcas. The woman was ordered to be kept in jail until her child was born, and thirty lashes, well laid on, were to be given. A negress was occasionally guilty of infanticide.

Before 1861, and particularly before 1830, there were somewhat frequent instances of manumission. But restrictions were imposed on the freedman. He was registered as to height, color, markings, etc., and a duplicate of the paper given him. Registration had to be repeated every five years. To live int he county he had to have the consent of the county court. He had a surname as well as a given name, and his marriages were recorded among those of the white people. It was the policy of Virginia to discourage the free negro from remaining in the state. He was too frequently idle and worthless, and his presence tended to make the slaves restless and demoralized. A request to remain, if by a freedman who stood well with the whites, was not likely to be turned down.

In 1830 the desire to get rid of the institution of slavery had become very strong in Virginia. The state was declining in wealth, and emigration tot he West and South was very heavy. About this time, 343 women of Augusta county signed a petition for immediate emancipation. A petition to the Assembly, dated 1827 and sent from Rockbridge, asked the removal of free negroes front eh state, and favors manumission and colonization. It went on to say that "the evils, both political and moral, which spring from the difference of color and condition in our population, are great and obvious. The blacks, in proportion to their number, are a positive deduction from our military strength, and impediment to the wealth and improvement of the country, and to the general diffusion of knowledge by schools; a source of domestic uneasiness and an occasion of moral degeneracy of character. Separated by an impassable barrier from political privileges and social respectability, and untouched by the usual incentives to improvement, they must be our natural enemies, degraded in sentiment and base in morals."

Another Rockbridge petition exhibits the contrast between 1790 and 1830, with respect tot he section of the state east of the Blue Ridge. The whites had increased from 314,523 to 375,935, but the blacks had increased from 288,425 to 457,013, being then in a majority. The tendency toward an Africanization of the Eastern District was causing much emigration of the whites. It was prophesied that a race war would result and cause a blotting out of the negroes. The petition asked for a special tax to create a fund to remove such blacks as were willing to go, and to purchase some others to send with them. It also asked that private emancipation be followed by removal.

In 1832 a bill for a general emancipation passed the lower house of the legislature, and lacked only one vote of going through the senate. The Western District of Virginia was almost unanimous for the measure. The value of the slave property was about one hundred million. Shortly after the defeat of this bill came the tragic insurrection in Southampton, whereby sixty white people lost their lives. An anti-slavery feeling spread int he North, and the many anti-slavery societies int he South were disbanded. The institution was given a new lease of life, and yet there saws still a strong economic opposition to slavery int he Western District, this name being given, until 1861, to the portion of Virginia west of the Blue Ridge.

A petition form this county in 1847 said it was believed there were 60 thousand of the free colored int he state, and it asserted the opinion that there would be 250 thousand of them in the year 1900. It recommended deportation to LIberia, and said that with few exceptions the freedmen were idle, worthless, and increasingly injurious to the slaveholders and the slaves. Henry Ruffner, a slaveholder, put forward a plan the same year. He found that slavery was driving away immigration, driving out white laborers, crippling agriculture, commerce, and industry, imposing hurtful social ideals upon the people, and that it was detrimental to the common schools and to popular education. His plan was to divide the state along the line of the Blue Ridge, eliminate slavery on the west side, and on the east side to introduce a policy of gradual emancipation, deportation, and colonization. John Letcher was also in favor of eventually keeping slavery out of the Western District. In the course of an interview at Washington College, General Lee said he and always favored gradual emancipation He had considered the presence of the negro and absolute injury to the state and a peril to its future. He thought it would have been better had Virginia sent her negroes into the cotton country.

In 1860, the imminence of civil war appreciated slave values and gave a stimulus to a more active selling of them in the cotton states. In the Gazette for 24 January 1860, William Taylor advertised for one thousand negroes for the Southern market. Another advertisement, dated 10 May 1860, read thus: "I wish to purchase 500 likely young negroes of both sexes for the Southern market, for which I will pay the highest market prices in cash. My address is Staunton or Middlebrook, Augusta county, Va. J. E. Carson. About this time advertisements of runaway slaves were somewhat a regular feature of the newspapers.

During the war of 1861 the conduct of the negroes was highly creditable to the race, and there were few misdemeanors among them. Many of the slaves showed great fidelity in staying with the families of their masters and working the farms. In one instance a master was about to join the Confederate army and had to leave five children behind him. His man slave told him to go on and he would himself see that things at home were attended to. The master was killed in battle, but the negro was faithful to his trust, and the children were enabled to go to school. A monument marked the grave of the old servant int he Timber Ridge burial ground.

American slavery was doomed by the war of 1861, no matter which side might triumphed. The Federal government resorted to emancipation as a war measure, and it was made permanent by a constitutional amendment. Yet it was not generally known that an emancipation act was passed by the Confederate Congress in the closing days of the war.

The slave was commonly known by a single name, instances of which were Mingo, Will, Jerry, Jude, Pompey, Dinal, Daphne, Rose, Jin, Nell, Let, Phoebe, Phillis, and Moll. ONe effect of emancipation was to ensure him a surname, which was often that of the family in which he had worked.

An interesting exception to a general rule was that of the Reverend John Chavis. In 1802 it was certified that he was free, decent, orderly,a nd respectable, and had taken academic studies at Washington College. Another was Patrick Henry, for whom Thomas Jefferson built a cabin on his land at Natural Bridge and left him in charge of the property, so that it might be adequately shown to visitors. Jefferson conveyed some land to him in fee simple and he lived on it till his death in 1829. Henry's will is on record at Lexington. He had the unique distinction of being a colored slaveholder, as the following document would show:

"Be it known to all whom these presents may come, that I, Patrick Henry, of the County of Rockbridge and State of Virginia having in the year of our Lord one Thousand eight hundred and fifteen purchased from Benjamin Darst of the town of Lexington a female slave named Louisa, and since known by the name of Louisa Henry; now, for and in consideration of her extraordinary meritorious zeal in the prosecution of my interest, her constant probity and exemplary department subsequent to her being recognized as my wife, together with divers other good and substantial reasons, I have this day in open court in the county aforesaid, by this my public deed of manumission determined to enfranchise, set free, and admit her to a participation in all and every privilege, advantage, and immunity that free persons of color are capacitated, enabled, air permitted to enjoy in conformity with the Laws and provisions of this commonwealth, in such case made and provided. And by these presents I do hereby emancipate, set free, manumit, and disenthrall, the said Louisa alias Louisa Henry from the shackles of slavery and bondage forever, for myself and all persons whomsoever, I do renounce, resign, and henceforth disclaim all right and authority over her as, or in the capacity of a slave. And for the true and earnest performance of each and every stipulation hereinbefore mentioned to the said Louisa, alias Louisa Henry, I bind myself, my heirs, executors, and administrators forever. In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand and affixed my seal this second day of December int he year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixteen. Patrick Henry."

In 1910 the negroes of Rockbridge were 16% of the population, and paid taxes on land.

Amy Timberlake, daughter of a negress brought from Africa, lived to a greater age than any other resident of Rockbridge, so far as information goes. She died in 1897 at the age of 107.

In the middle course of Irish Creek was a considerable community sometimes known as the "brown people." They lived the simple life in their little log cabins which dotted the valley nd the bordering hillsides. In the veins of many of them was the blood of the Indian as well as that of the African, but the Caucasian type was dominant.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments)

| Receive

updates ( subscribers) |

Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |