|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 14 , Issue 462012Weekly eZine: (376 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

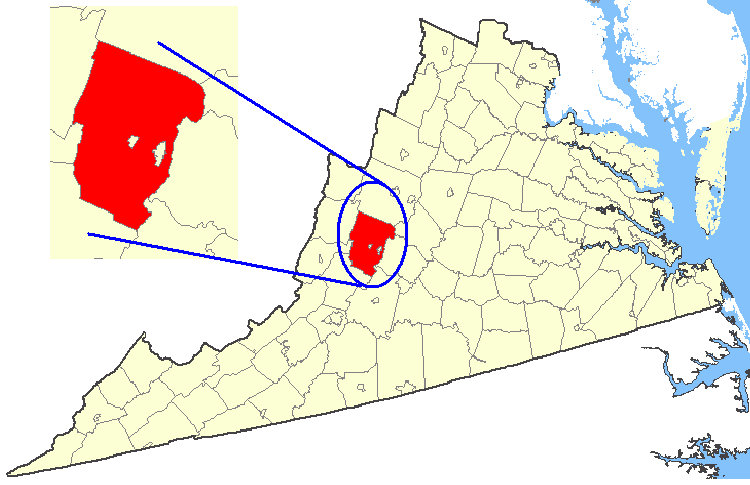

History of Rockbridge County, Virginia

According to Oren Frederic Morton's 1912, The History of Rockbridge County, Virginia, the history of the upper valley of Virginia the European background is to be sought in the southwest of Scotland and the north of Ireland, in the Strathclyde and in Ulster, respectively. In each there were mountains, usually deforested and sometimes gaunt and gloomy, which were similar in height to the elevations rising above the floor of the Valley of Virginia. To learn more of the Valley of Virginia, we need to study more of the Scottish and Ulstermen of the British Isles.

Each had fine swift streams, comparable in volume to the North River at Lexington, or to its tributary, the Buffalo. In each the surface alternates from mountain to valley, and from broken ridges to small tracts comparatively level. The soil was often stony, sometimes excessively os, and in general it was not highly fertile or easily tilled. The mean annual temperature was fifty degrees, as against fifty-four at lexington. The winter temperature was noticeably milder than that of Rockbridge, but the summer was very much cooler, begin scarcely warmer as a Rockbridge May. The climate, cool, cloudy, and humid was suited to grass, oats and root crops, and either region was better adapted to grazing than to tillage.

These descriptions of the countries on the two sides of the NOrth Channel suggested a certain measure of resemblance to the Shenandoah Valley and the Appalachian uplands. The degree of resemblance goes far to explain why the immigrant from Ulster had so successfully adapted himself to Appalachian America.

The population of the British Isles was mainly of the elements that held possession in the days of Caesar. The invading bands of Anglen, Saxons and Jutes overran the lowlands on the installment plan, and full success did not come for many years. By assimilating with the natives they gave the country a new language and new institutions. But whether Highlanders or Lowlanders, the Scottish people were essentially one with respect to origin. The Lowlands gave up the old speech, while the Highlands retained it. And it was worthy of notice that the dialect of English spoken in the Lowlands differed little from the everyday speech of the north of England.

The Scottish people of this period were tall, lean, hardy and sinewy. They were ignorant of high living and had good nerves and digestion. They were combative, and not easy to get along with to those who did not fall in with their ways. They were strong-willed and strongly individualistic, and were therefore fierce sticklers for personal liberty. By the same token they were more democratic in thought than the English and were less inclined to commercial pursuits. If you challenged a Scotsman's views of right and wrong, it roused him to speedy action. His morality had a solid groundwork, being based on general education and on regular attendance at his house of worship. Outwardly he was unemotional and not given to displays of affection. But there was more sunshine in his life than was commonly believed.

Scotland united with England on her own terms. Ireland, on the contrary, was subdued, and to the impoverishment by absentee landlords was added the oppression of the harsh laws with respect to religion and industry. It was under James the First, whose reign began in 1603, an unsuccessful rising of the Irish was punished by the confiscation of more than 3 million acres of Ulster soil. This area had become partially depopulated, and the english ing made successful efforts to re-people it with settlers from the other side of the Irish sea. Some lawless Highlanders and flocked in, but they were a most undesirable element, and preference was now given tot he Lowlanders.

When the descendants of these colonists began coming to America, they were called Irish for the very practical reason that they came from Ireland. Irishmen of the original stock were scarce in the United States before the enormous immigration caused by the potato famine of 1845. The term Scotch-Irish came into use to distinguish the earlier inflow format he later. The term Scotch-Irish implies that the people thus styled were the descendants of Scotchmen who settled in Ireland. It is only true in part. The Scotch of Strathclyde were the most numerous element and they gave their impress to the entire mass. But there were nearly as many settlers format he north of England, and there were a few from Wales. There were also not a few Huguenot refugees from France. It was the talented French Protestants, coming at the instance of William of Orange, who introduced the linen industry into Ulster and made it the basis of its manufacturing prosperity. Some of the native Irish blended with the immigrant population. As far as religion was concerned, there was none. The newcomers were Presbyterians, while the natives were Catholics. In Ulster these two elements had never ceased to dislike one another.

It was not a characteristic of the Ulster people to turn a cold shoulder toward those who agreed with them. J. W. Dinsmore observed that the Ulsterman had the steadfastness of the Scot, the rugged strength and aggressive force of the Saxon, and a dash of the vivacity and genius of the Huguenot. When the Ulsteman came to America he spoke the Elizabethan type of English, which the Irish adopted as an incident in their conquest.

As to religion, the infamous "Black Oath" of 1639 rehired all the Protestants of Ulster who were above the age of sixteen to bind themselves to an implicit obedience to all royal commands whatsoever. This display of autocratic tyranny led multitudes of men and women to hide in the woods or to flee to Scotland.

The Presbyterian minister was expected to preach only within certain specified limits, and was liable to be fined, deported, or imprisoned. He could not legally unite a couple in marriage, and at times he could preach only by night and in some barn.

It was in 1689 the Irish rose in behalf of the deposed king of England, James the Second. Protestants were shot down at their homes. Women were tied to stakes at low tide, so that they might drown when the ocean waves came back. Londonderry was besieged by a large army, but was defended with a desperation unsurpassed in history. The british Parliament enforced its anti-popery laws against the Presbyterians as well as the Catholics. The time had not yet come then a Presbyterian might sell religious books, teach anything above a primary school, or hold civil or military office. There was no general redress of grievances until 1782.

The persecution was industrial as well as religious. English laws discriminated against Ulster manufactures, particularly the manufacture of woolen goods. This flourishing business was ruined by a law of 1698.

In view of such a hounding persecution, it might seem strange that the people of Ulster could retain a shred of respect for their government. Yet, as citizens of the British Isles, they professed loyalty to the crown. From 1704 to 1760 the English monarch was a figurehead in almost the fullest sense of the term. The resentment of the Ulster people was directed against the corrupt clique that governed in the king's name. There was a ruling English party in Ulster. Episcopalians were more numerous than Presbyterians, in at least two of the seven counties, and the Catholic population was equal to the Protestant.

The straw that broke the camel's back for the Ulster people was the display of greed shown about 1723. A large quantity of land given to favored individuals was offered only on 31 year leases and at two to three times the former rental. An emigration to America, which really began about 1718, assumed large dimensions. For the next half century or until interrupted by the war for American independence, the outflow was reckoned by some authorities as high as 300,000. Ulster was drained of the larger and best part of its population. The fundamental reasons for the exodus were stated in a sermon delivered on the eve of the sailing of a ship: "To avoid oppression and cruel bondage; to shun persecution and designed ruin; to withdraw form the communion of idolators; to have opportunity to worship God according to the dictates of conscience and the rules of his Word."

It was throughout this period of heavy emigration from Ulster that there was almost as large a tide of Germans form the valley of the upper Rhine, inclusive of Switzerland. But until near the outbreak of the Revolution, the German settlers in Rockbridge were very few.

The colonials of 1716 were overwhelmingly of English origin, but there was a sprinkling of Scotch, Welsh, Irish, Hollanders, and French Huguenots. Each colony was an independent country with respect to its neighbors. The roads were bad and bridges few, traveling was slow and difficult. All knowledge of the outside world was elementary. Africa was visited only in the interest of the slave trade, and Australia was unknown. Every sea was infested with irate vessels.

In Virginia we find that its 100,000 people, of whom one-fourth were negro slaves, lived almost exclusively to the east of a line drawn through Washington and Richmond. Williamsburg was merely a village. Norfolk was smaller than Lexington. Virginia was strictly an agricultural region, and the growing of tobacco was by far the dominant interest. The society was not democratic. The head of the scale was the tidewater aristocracy, feudalistic and reactionary, polite to women, profane among its own kind, fond of horses and sports, and indifferent to books. These people constituted the one and only ruling class, and the public business thrown upon them induced a good degree of practical intelligence. Below them were the professional men, tradesmen, small farmers, and white servants, some of the latter having come to America as convicts.

This was the outline of the America of 1716. It was instinctive in the human species to look with suspicion or dislike on those whose ways were different from out own. The Ulstermen were very much inclined to keep together. We are the better able to understand why some of the Ulster people lived a while in Pennsylvania. It was largely outweighed by its narrowness, and so the Ulstermen pushed southward as well as westward, gradually occupying all Appalachian America front eh Iroquois country south of Lake Ontario to the Cherokee country on the waters of the upper Tennessee. In this way the inland frontier of America was pushed rapidly forward. Otherwise the year 1776 might have found inVirginia but a handful of people west of the Blue Ridge.

Valley of Virginia - Borden Land Grant

In early September 1737, a small party of home seekers were in camp on Linville Creek in what was then Rockingham county. They were journeying by the trail that was sometimes called the Indian Road, and sometimes the Pennsylvania Road. In this company of travelers were Ephraim McDowell, a man then past the meridian of life, his son John, and a son-in-law, James Greenlee.

They traveled with their families and their destination they had in view was South River. James, another son of Ephraim, had come in advance and planted a little field of corn in that valley opposite Woods Gap.

The McDowells had come from Ulster in "the good ship, George and Ann," landing at Philadelphia, September 4, 1729, after being on the Atlantic 118 days. It was a slow voyage. even in those days of sailing vessels, and yet it was not unusual. As in many other instances among the Ulster people, Pennsylvania was only a temporary home. The country west and southwest of the metropolis, as far as the Susquehanna and the Maryland line, was well-populated, according to the standard of that agricultural age. Land was relatively high in price, and so the newcomers, if they had to move inland to the advance line of settlement, often thought they might as well look for homes in "New Virignia."

John Lewis, a kinsman to the McDowells, had founded in 1732 the nucleus of the Augusta settlement, and by this time several hundred of the Ulster people had located around him. Religion was not free in Virginia, but it was doubtless the belief of the newcomers that the planters of Tidewater, who were the rulers of the colony, would not deem it wise to molest them in their adherence to the Presbyterian faith.

A young man wrote to his sister in Ireland, in 1729, that gives us a look of what Pennsylvania was like back in 1729. The writer pronounced Pennsylvania the best country in the world for tradesmen and working people. Land was twenty-five cents to $2.50 an acre, according to quality and location, and wa rapidly advancing because of the large and varied immigration. His father, after a long and cautious search, made a choice about thirty miles from Philadelphia. For 500 acres of prime land, inclusive of a small log house, a clearing of twenty acres, and a young orchard, the purchase price was $875. In the meantime the father had rented a place and put 200 acres in whoa, a crop that commanded fifty cents a bushel. Oats were twenty-eight cents a bushel, and corn was twenty-five cents. The laboring man had about twenty cents a day in winter. In harvest time he was paid thirty cents a day, this service including the best of food and a pint of rum. At the end of his swath he would find awaiting him some meat, either boiled or roasted, and some cakes and tarts. One to two acres could be plowed in a day, which was twice the speed that could be made in Ireland. A boy of thirteen years could hold the implement, which had a wooden moldboard. Horses were smaller than in Ireland, but pacing animals could cover fifteen miles in an hour's time. At philadelphia, then a little city of perhaps 5,000 inhabitants, all kinds of provisions were extraordinarily plentiful. Wednesdays and Saturdays were market days. Meat of any kind could be had for two and one-half cents a pound. Nearly every farmhouse had an orchard of apple, peach and cherry trees. Wheat yielded twenty bushels tot he acre and turnips 200. The writer corrects several false reports about the colony which had been carried to the other side of the ocean. he said there had as yet been no sickness in the family, and that not a member of it was willing to live in Ireland again. The cost of passage to the mother country was $22.50.

There must have been some regret among the Ulster people that it was not easy to secure a foothold in such a thriving district as the Philadelphia region. But America as a land of opportunity, whether on the coast or in the interior.

It was after the McDowells had established their camp on Linville Creek that an incident occurred which led to some change in destination. A man giving his name as Benjamin Borden came along and arranged to spend the night with them. He told them he had a grant of 100,000 acres on the waters of the James, if he could ever find it. To the man who could show him the boundaries he would give 1,000 acres. John McDowell replied that he was a surveyor and would accept the offer. A torch was lighted, McDowell showed his surveying instruments and Borden his papers. Each party was satisfied with the representations made by the other. At the house of John Lewis, where they remained a few days, a more formal contract was entered into, the phraseology of which indicates that it was written by Borden.

The lands were at the Chimney Stone and on Smith Creek and laid in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Accompanied by John McDowell, Borden went on from Lewis's and camped at a spring where Midway now is. From this point the men followed the outlet of the spring to South River, and continued to the mouth of that stream, returning by a course. Borden could see that he was within the boundaries of his grant. John McDowell built a cabin on the farm occupied by Andrew Scott in 1806. This was the first white man's settlement in the Borden Tract. The McDowells had never heard of this grant, and it had been their intention to locate in Beverly Manor.

All Virginia west of the Blue Ridge was until the establishment of Augusta and Frederick in 1738 a part of Orange county, and the seat of local government was near the present town of Orange. The Borden Tract laid in the Indian country. It was not until 1744 that the treaty of Albany was superseded by that of Lancaster. The former recognized the Blue Ridge as the border of the Indian domain. The latter moved the boundary back tot he Indian Road, already mentioned. The red men were within their rights when they hunted in the Valley, or passed through on war expeditions. In point of fact the whites were trespassers. But the American borderer had seldom stood back from this form of trespass whenever he was in contact with desirable wild land.

Borden remained about two years on his grant, spending a portion of the time with a Mrs. Hunter, whose daughter married a Green, and to whom Borden gave the place they were living on when he left. There is a statement that Borden sailed to England and brought back a large company of settlers. This is very doubtful, as such action was not necessary. Borden did advertise his lands, and to such effect that more than 100 families located not eh tract within the two years. But immigrants were arriving at Philadelphia almost every week, sometimes tot he number of hundreds, and efficient advertising was certain to bring the desired results. When Borden went back to his home near Winchester, he left his papers with John McDowell, to whose house many of the prospectors came in order to be shown the parcels they thought of buying. Three years later he died on the manor-place he had patented in 1734.

| View or Add Comments (0 Comments)

| Receive

updates ( subscribers) |

Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |