|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 14 , Issue 512012Weekly eZine: (366 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

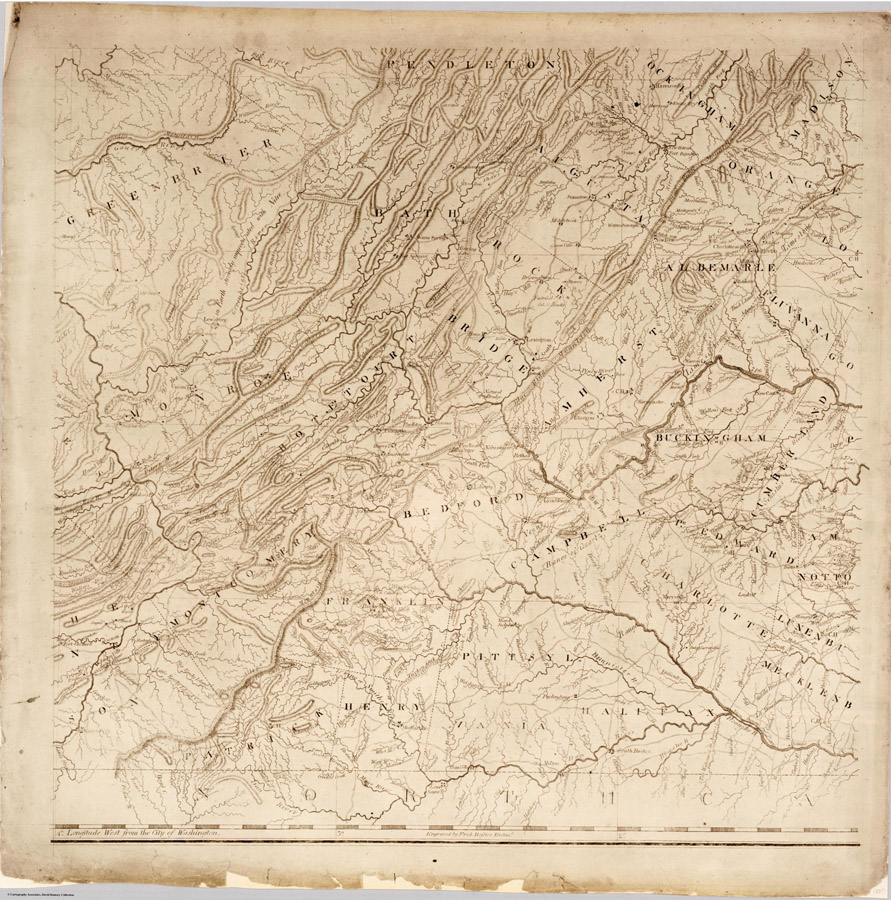

History of Rockbridge County, Virginia - Strife With the Red Man

We are continuing where we left off last week when we were speaking of stories of "Strife With the Red Man" in the Rockbridge County, Virginia area. Did we speak of the assemblage at Big Spring last week? If not, it begins this week's continuation of the Red man's strife in Virginia.

A number of the people of the valley were attending a meeting at Timber Ridge, the day being Sunday. Those gathered at Cunningham's were in a field, saddling their horses in great haste, in order to join their friends at the meeting house. The secreted foe seized the coveted moment to cut them off from the blockhouse. The scene which followed was witnessed by Mrs. Dale from a covert on a high point. When the alarm reached her she mounted a stallion colt that had never been ridden, but which proved as gentle as could be desired. The foe was gaining on her, and she dropped her baby into a field of rye. In some manner she afterwards eluded the pursuers, but was too late to reach the blockhouse. A relief party found the baby lying unhurt where it had been left. Such was the story, but it is more probable that the mother recovered the child herself after the raiders had gone away.

While the saddling was going on two men started up the creek to reconnoiter, but were shot down, as were also two young men who went to their aid. The onslaught of the foe was immediate, and each redskin singled out his victim. Mrs. Dale said the massacre made her think of boys knocking down chickens with clubs. Some tried to hide in the big pond or in thickets of brush or weeds. All who attempted to resist were cut down. Cunningham himself was killed and his house was burned. There was no record that the Indians suffered any loss.

According to a Samuel Brown, sixty to eighty persons were killed in the two Kerr's Creek raids, and twenty-five to thirty carried away. This was an overstatement. William Patton, who was at Big Spring the day after the massacre, helping to bury the dead, said these were seventeen in number. He added that the burial party was attacked. Among the prisoners, according to Mr. Brown, were Mrs. Jenny Gilmore, her two daughters, and a son named John; James, Betsy, Margaret and Henry Cunningham; and three Hamiltons, Archibald, Marian and Mary. One of the Cunninghams was the girl scalped in the first raid. She returned from captivity and lived about forty years afterward, but the wound finally developed into a cancerous affection. According to a rather sentimental sketch in one of the county papers, Mary Hamilton was among the killed, and John McCown, her lover, died two years later of a broken heart and was buried by her side at Big Spring. Mr. Waddell said she had a baby in her arms when she was captured. She threw the infant into the weeds, and when she returned from the Indian country she found tis bones where she had left it.

On the afternoon of the second tragedy, the Indians returned to their camp on North Mountain, where they drank the whiskey found at Cunningham's still. They became too intoxicated to have put up a good resistance to an assault. Yet they had little to fear, as there was a general panic throughout the Rockbridge area. Next day two Indians went back, either to see if they were pursued for to look for more liquor. It seems to have been on this occasion when Mrs. Dale saw them shoot at a man who ventured to ride up the valley. When he wheeled they clapped their hands and shouted. This incident constituted the attack mentioned by William Patton.

During the march to the Shawnee towns, the Indians brained a fretful child and threw the baby on the shoulders of a young girl who was killed next day. At another time, the prisoners were made to pass under an infant pierced by a stake and held over them. On still another occasion, while some of the prisoners were drying a few leaves of the New Testament for the purpose of preserving them, a savage rushed up and thew them into the camp fire. When the column arrived at the Scioto, the captives were ironically called upon to sing a hymn. Mrs. Gilmore responded by singing Psalm 137 as she had been won't to do at Timber Ridge. It was related that she had stood over the corpse of her husband, fighting desperately and knocking a foeman down. Another Indian rushed up to tomahawk the woman, but his comrade said she was a good warrior, and made him spare her. She and her son were redeemed, but she never knew what became of her daughters. Several other captives were also returned.

Some account of the massacres on Kerr's Creek was related many years afterward by Mrs. Jane Stevenson. She was then living in Kentucky,a nd her story was reduced to writing by John D. Shane, a minister. Mrs. Stevenson, who was born November 15, 1750, spoke of a girl four months older than herself taken at the age of seven years and held until the Bouquet delivery in 1764. The children had gone out with older companions to gather haws, and the narrator escaped capture only by not going so far as the others. At the first raid an aunt who had two children escaped into the woods, the Indians going down the river. But on the second occasion, this aunt and her three children were taken and an uncle and a cousin were killed. Two of the children died in captivity, but the aunt and the third child were restored. In this second raid Mrs. Stevenson thought the Indians had the ground all spied out, and followed a prearranged program. She says they came in like racehorses, and in two hours killed or captured sixty-three persons. One of the prisoners was James Milligan. He escaped on Gauley Mountain and reported having counted 450 captives, as the total collected in the entire raid. Two small boy captives were James Woods and James McClung, and after their return they had the condition of their ears recorded int he clerk's office at Staunton. Cropping the human ear was in those days a form of punishment, and the person who had an ear mutilated by accident or in a fight went before the county court to have the fact certified, so as not to be regarded as an e-convict.

Mrs. Stevenson was a daughter of James Gay, who lived seven miles from Kerr's creek. Her mother, whose maiden name was Jean Warwick, was killed by the Indians about 1759. Mrs. Stevenson related that the adult male members of the Providence congregation carried their guns to meeting as regular as the congregation went. Alexander Crawford was killed about fifteen miles from the meeting house in the direct of Staunton. The narrator said that when the Indians took Kerr's Creek settlement a second time they were greatly bad. and that it almost seemed as though they would make their way to Williamsburg. The shot the cows mightily with bows and arrows. She moved to Greenbrier in 1775, where there was never a settlement of kinder people, these being great for dancing and singing. But her statement that William Hamilton and Samuel McClung were the only Greenbier settlers who were not Dutch and half-Dutch, cannot be correct at all, unless true of the particular locality where these men settled. It was also to be remembered that she was not yet grown at the time of the doings on Kerr's Creek. As for Milligan, he must have been able to see more than double in order to count 450 prisoners led away by probably not more than one-fifth as many warriors.

It was not known that the settlers on Kerr's Creek and themselves given cause to make their valley a special mark for Indian vengeance. The native venerated the home of his forefathers, and would make a long and perilous journey for no other purpose than to gaze upon a spot known to him only in boyhood or perhaps only by tradition. It may have been resentment, pure and simple, that led him to visit his fury upon the palefaces who had crowded him out of a choice portion of his hunting grounds. So it was not to be wondered at that the children attending Bunker Hill schoolhouse near Big Spring and a superstitious horror of the field where the massacre took place.

The treat which ended the Pontiac war stipulated that the Indians should return their white captives, and these were delivered to Colonel Bouquet in November, 1764. However, there were instances where the return did not take place until some time later. According to William Patton, the foray of 1763 was the last that took place on Rockbridge soil. Yet in the Dunmore war, and in the hostilities that continued intermittently from 1777 to 1795, there was always the possibility of still other incursions. The Indian peril was forever removed form Rockbridge by the treaty of Greenville, in 1795, which was secured by General Wayne's victory in the battle of the Fallen Timbers.

The Dunmore war of 1774 was caused by the extension of white settlement into the valley of the Ohio. It was waged between the Virignia militia and a confederacy headed by the Shawnees. Rockbridge men served in the companies from Augusta and Boteourt, and helped to gain the memorable victory of Point Pleasant.

There was only one recorded instance where an Indian was held in slavery in Rockbridge. This was in 1777.

It was said that several of the family names on Kerr's Creek were blotted out as a result of the scenes in 1759 and 1763. The record books for 1758-60 indicate an exceptional mortality in the Rockbridge area. Some of names that appeared to belong to this region, but not known that violence was the cause of all the deaths indicated, were:

- Jacob Cunningham, will probated March 18, 1760.

- Isaac Cunningham, died 1760, Jean, administrator.

- Benjamin, orphan of John Gray, 1760.

- Samuel, orphan of Alexander McMurty, becomes ward of Matthew Lyle, 1759.

- James McGee, will probated August 20, 1759, Robert Hall, administrator.

- James Rogers, died 1760, Ann Rogers administratrix with Walter Smiley on her bond.

- James Stephenson, died 1760.

- Thomas Thompson, died 1760.

- John Winyard, will probated, November 15, 1758, Barbara, executor.

- Samuel Wilson, died 1760.

- James Young, died 1760.

This second party was so successful that it could not take back all its pelts, and a portion was deposited in a "skin-house" in what was Green county, Kentucky. Ammunition ran low, and all but five returned the next February. One of the five fell ill, and a comrade took him to the settlements. Two of the remaining three of the camp guard were captured by Indians. The seventeen returned after about three months, and continued to hunt and explore, some of the names they gave to certain localities. Late in the summer of 1772 their camp was plundered by Cherokees at a time when they were absent from it, but hunting continued till the end of the season. The only names that can certainly be identified as belonging to Rockbridge were those of Robert Crockett and James Graham, of the Calfpasture. Another member was james Knox, and not General Knox, of Washington's army, for whom Knoxville in Tennessee was named. Crockett, who lost his life during the first expedition, was said to have been the first white man killed in that state. The wives of Governor Bramlette and Senator J. C. S. Blackburn, of Kentucky, were granddaughters of Graham. | View or Add Comments (0 Comments) | Receive updates ( subscribers) | Unsubscribe

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |