|

Moderated by NW Okie! |

Volume 15 , Issue 12013Weekly eZine: (366 subscribers)Subscribe | Unsubscribe Using Desktop... |

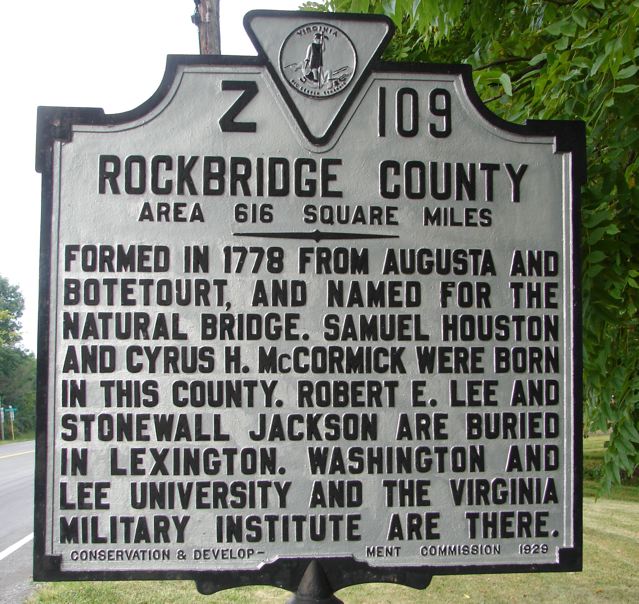

History of Rockbridge County, Virginia - War For Independence

In chapter XI of Oren F. Morton's book, History of Rockbridge County, Virginia, we learn of Rockbridge county and its part in the war for independence. We also learn the causes of the war; the Fincastle and Augusta Resolutions; Virginia in the Revolution; campaign of 1781; and Pensioners.

They say the underlying cause of the American Revolution was similar to that which forced our country into her struggle with Germany. That it was a protest against autocracy. We know that the American colonies were founded when the relations between the king and his people had not reached a settled basis. It had always been the English practice for the people of each community to manage their local affairs, and this principle was followed by the immigrants who peopled the colonies. Trouble began during the conflict between king and Parliament in the time of Cromwell. It assumed serious dimensions during the reign of James II (1658-8, but did not become acute until the accession of George III in 1760. it was several decades before the beginning of the outflow from Ulster, when few people had bee coming to the colonies. The Americans of 1725 had begun to feel that they were already a people distinct from the English. During the quarrel that began with the ending of the Old French War, the colonies held that they were a part of the British Empire. But the British government viewed them as belonging to it, and consequently as possessing rights of a lower grade.

To the colonials the person of the monarch was the visible tie that joined them to the British Empire. By a legal fiction the king was an impersonation of the state, and only in this sense did they consider that they owed any allegiance to him. The Americans understood Britain to be made up of king, Parliament, and commons; each American colony to be made up of governor, a representative of the crown, legislature and people. Under Anne and the first and second Georges, the monarch was a mere figure-head. The actual government was in the hands of a corrupt oligarchy. George I was a German, and could speak no English, except when he swore at his troopers. George III began his reign with German ideas of divine right and absolutism, and these he determined to carry into practice. Local self-government had declined markedly in England. It was only a few persons who enjoyed the elective franchise. Parliament was not representative of the people, and by open bribery the king was able to control legislation. The general mass of the english people were at tis time ignorant, brutal, and besotted, and they were apathetic toward their political rights. There was a higher level of intelligence in America than in England.

Under kingcraft, as interpreted by George III, the people were to obey the crown and pay taxes. Functions of a public nature were held to inhere in the sovereign. Activities were to start from above, not from below. The Americans contended that the central government could properly act only in matters concerning the empire as a whole. They did not concede that parliament had any right to tax any English-speaking commonwealth that had its won law-making body. On the one side of the ocean there was a rising spirit of democracy. On the other, there was an ebbing tide, and a divine-right monarch was in the saddle. A clash was inevitable.

To the Americans there were several particular sources of annoyance. It was an anomaly for any other person than an American to be the governor of an American colony. But in the crown colonies, of which Virginia was one, the governor was an imported functionary, and on retiring from office he usually went back to Britain. As a rule he was a needy politician, did not mingle socially wight he Americans, and in his official letters he was nearly always abusing them. Another annoyance was the Board of Trade, a bureau which undertook to exercise a general oversight in America. It cared little for good local government. It sought to discourage any industry which might cause a leak in the purse of the British tradesman. Its one dominant aim was to see that the colonies were meek and to render them a source of profit to the British people and the British treasury.

Even after the controversy had become one of bullets instead of words, the prevailing sentiment in America was not in favor of political separation. The colonials felt a pride in their British origin. They recognized that a union founded on justice was to the advantage of every member of the British Empire. At the outset, the Americans fought for the rights which they held to be common to all Englishmen. In this particular they had the good will of a large section of the people of England. It was the autocratic attitude of the king that made separation unavoidable.

American independence was proposed and accomplished by a political party known in Revolutionary history as the Whig. It was opposed by a reactionary party known as the Tory. But in the Whig party itself was a conservative as well as a progressive wing. The former consented to a separation, but otherwise it wanted things to remain as they were. The progressives had a further aim. They were bent on establishing a form of government that was truly democratic. The progressives prevailed, and yet the work they cut out was only well under way when independence was acknowledged. "The Revolution began in Virginia with the rights of America and ended with the rights of man."

The basic origin of the Revolution was political. In the Southern colonies there was not an economic cause also, as was the case in New England. The experts from Virginia touched high water mark in 1775, in spite of the long quarrel between the governor and the people.

We find that the Ulster people were naturally more democratic than the English, and there was nowhere inAmerica that the democratic feeling more was more pronounced than along the inland frontier. The Scotch-Irish element generally rallied to the support of the Wig party, and was a most powerful factor in its ultimate success. The Tory influence was strong in the well-to-do classes along the seaboard, particularly among men in official and commercial life. Virginia was somewhat exceptional in this regard. It was practically without any urban population. The planter aristocracy upheld the Whig cause, and as it was the ruling class, it carried the colony with it. It must be added, however, that the planters of Tidewater cast their lot with the conservative wing of the party. It was under the lead of such men as Jefferson and Madison, residents of Middle Virginia, that the state capital was taken away form the tidewater district in 1779. The progressive Whigs east of the Blue Ridge found a strong ally in the population west of that mountain.

The resolutions adopted at Fort Chiswell, the county seat of Fincastle, were so closely in harmony with the views of the people in the Rockbridge area that we present them in this chapter. The address by the Committee of freeholders was signed 20 January 1775, and was directed to the Continental Congress. The chairman was William Christian. Other prominent members of the committee were William preston and Arthur Campbell. Of the fifteen men, all were officers except the Reverend Charles Cumings.

The Resolution

"We assure you and all our countrymen that we are a people whose hearts overflow with love and duty to our lawful sovereign, George III, whose illustrious House, for several successive reigns, have been the guardian of the civil and religious rights and liberties of British subjects as settled at the glorious revolution (of 1688); that we are willing to risk our lives in the service of His Majesty for the support of the Protestant religion, and the rights and liberties of his subjects, as they have been established by compact, law, and ancient charters. We are heartily grieved by the differences which now subsist between the parent state and the colonies, and most heartily wish to see harmony restored on an equitable basis, and by the most lenient measures that can be devised by the heart of man. Many of us and our forefathers left our native land, considering it as a kingdom subjected to inordinate power and greatly abridged of its liberties; we crossed the Atlantic and explored this then uncultivated wilderness, bordering on man nations of savages, and surrounded by mountains almost inaccessible to any but those very savages, who have incessantly been committing barbarities and depredations on us since our first seating the country. Those fatigues and ravages wet patiently encounter, supported by the pleasing hope of enjoying those rights and liberties which had been granted to Virginians, and were denied us in our native country, and of transmitting them inviolate to our posterity; but even to these remote regions the hand of unlimited and unconstitutional power hath pursued us to strip us of that liberty and property, with which God, nature, and the rights of humanity have vested us. We are ready and willing to contribute all in our power for the support of his Majesty's government, if applied to constitutionally and when the grants are made to our representatives, but cannot think of submitting our liberty or property to the power of a venal British parliament, or tot he will of a corrupt British ministry. We by no means desire to shake off our duty or allegiance to our lawful sovereign, but on the contrary, shall ever glory in being the lawful subjects of a Protestant price, descended from such illustrious progenitors, so long as we can enjoy the free exercise of our religion as Protestant subjects, and our liberties and properties as British subjects.

"But if no pacific measures shall be proposed or adopted by Great Britain, and our enemies will attempt to dragoon us out of those inestimable privileges, which we are entitled to as subjects, and reduce us to slavery, we declare that we are deliberately ad resolutely determined never to surrender them to any power upon earth but at the expense of our lives.

"These are our real though unpolished sentiments, of liberty and loyalty, and in them we are resolved to live and die."

The opening lines of the address do not make the impression then that they were intended to make in 1775. The portraiture of George III was the direct opposite of that given in the Declaration of Independence. The latter document censures only the king, while the address vents it indignation on the king's ministry and on Parliament. But the committee appear to draw a distinction between the king as a man and the king as a sovereign. In the former respect, George III was a very mediocre person, obstinate and narrow-minded. In the latter respect he was an impersonation of the state, and to the state every patriotic citizen owed allegiance.

Thomas Lewis and Samuel McDowell were delegates tot he Virginia Convention of March, 1775. The instructions given to them by Augusta county, February 22, contained the following sentences:

"We have a respect for the parent state, which respect is founded on religion, on law, and the genuine principles of the constitution. These rights wet are fully resolved, with our lives and fortunes, inviolably to preserve; nor will we surrender such inestimable blessings, the purchase of toil and danger, to any ministry, to any parliament, or any body of men upon earth, by whom we are not represented, and in whose decisions, therefore, we have no voice.

And as we are determined to maintain unimpaired that liberty which is the gift of Heaven to the subject of Britain's empire, we will most cordially join our county men in such measures as may be deemed wise and necessary to secure and perpetuate the ancient, just, and legal rights of this colony and all British America."

A memorial from committee of Augusta, presented to the state convention 16 May 1775, is mentioned in the journal of that body as "representing the necessity of making a confederacy of the United States, the most perfect, independent, and lasting, and of framing an equal, free, and liberal government, that may bear the trial of all future ages." This memorial was pronounced by Hugh Blair Grigsby the first expression of the policy of establishing an independent state government and permanent confederation of states which the parliamentary journals of America contain. The men who could draw up papers like these were not the ones to stand back from sending, as they did, 137 barrels of four to Boston for the relief of the people of that city in 1774. A savage act of Parliament had closed their port to commerce.

Even during the Indian war of 1774 there were very strained relations between the House of Burgesses and the Tory governor. In the spring of 1775, the administration of Dunmore was virtually at an end, and the Committee of Safety was managing the government of the state.

With respect to Virginia soil there were three stages in the war for American Independence. The first was confined to the counties on the Chesapeake, continued but a few months, and closed with the expulsion of Dunmore soon after his burning of Norfolk on New Years day, 1776. The invasion by Arnold began at the very close of 1780, and ended with the surrender of Cornwallis in October, 1781. The warfare wight he Indians continued intermittently from the summer of 1776 until after the treaty with England in 1783. Except int he southwest of the state, the red men rarely came east of the Alleghany Divide. The British did not come across the Blue Ridge, and only once did they threaten to do so. consequently the rock bridge area did not itself become a theatre of war.

But Rockbridge took an active part in the Revolution. At the outset of hostilities Augusta agreed to raise four companies of minute men, a total of 200 soldiers. William Lyle, Jr., was the lieutenant of the Rockbridge company, and William Moore was its ensign. We do not know the name of the captain, but he colonel was George Mathews, a native of Rockbridge. As the commander of the Ninth Virginia Regiment in the Continental service, Mathews distinguished himself in Washington's army until he and his 400 "tall Virginians" were outflanked during the fog that settled not he field of Germantown and compelled to surrender. Probably a number of Rockbridge men were in this regiment, but there is no positive information. It was in the militia organizations, and then only for two or three months at a time that most of the Rockbridge soldiers saw military duty.

The first active service on the part of men of this county was in the summer of 1776, when the militia under Captain John Lyle and Captain Gilmore marched under Colonel William Christian in his expedition against the Cherokees. He was gone five months, and accomplished his purpose without actual fighting, although five towns were destroyed. The companies of John Paxton and Charles Campbell were in the column of 700 men that reached Point Pleasant in November, 1777. Major Samuel McDowell was aline officer in this force, and his men began their march from the month of Kerr's Creek. General Hand was to march against the towns on the Scioto. Deciding that it was too late in the season and that provisions were too low, that leader contented himself with announcing the surrender of Burgoyne and then dismissing the militia, who reached home late in the next month. Next spring, Captain William McKee was in command at Point Pleasant. It was another Rockbridge company, under the command of Captain David Gray, that marched to the relief of Donally's fort when the news came that it was attacked by the Shawnees. Captain William Lyle also campaigned on the frontier.

The British invasion of 1781 was a more serious menace, though. It was necessary to preface the account of it with a glance at the fighting south of Virginia. After the battle of Monmouth in the summer of 1778, the British leaders made no serious demonstration against Washington's army,a nd their fleet made them quite safe at New York, which was almost the only ground they held in the North. The war in this quarter was a stalemate, and the British turned their attention to Georgia and the Carolinas. In these colonies the Tories were as numerous as the Whigs. Savannah was taken and then Charleston. After the second disaster there was no field army to contend with the enemy, and South Carolina and Georgia were overrun. While General Lincoln was besieged in Charleston, the Seventh Regiment of Virginia continentals under Colonel Buford whereon their way to reenforce him. But they were surprised at Waxhaw, no quarter was given, and they were cut down by the dragoons of Colonel Tarleton. After dusk some of the troopers, who were generally Tories, returned to the scene of the massacre, and where they found signs of life, they bayonetted the hacked and maimed. Captain Adam Wallace was among the slain. Several other Rockbridge men were either killed or wounded. The inhuman cruelty shown on this and other occasions by Tarleton made him an object of bitter hatred. He thought German methods of warfare the proper ones to use against the Americans, and the resentment he did so much to arouse was not entirely extinguished at the outbreak of the war of 1917.

It was a few months later a new American army, advancing from the north, was overthrown at Camden. At the close of 1780, when the fortunes of the Americans in the South were at a low ebb, General Greene, a leader of signal ability, was given command in all the colonies south of Pennsylvania and New Jersey. But the wreck of the army defeated at Camden was small, half-naked, and poorly equipped. The British and Tories were in much superior numbers and did not lack for clothing and munitions. Nevertheless, there was a turn in the tide. At the Cowpens, the right wing of the American army nearly destroyed a force under Tarleton, and 600 prisoners were sent to Virginia. Greene made a masterly retreat across North Carolina, closely pursued by Cornwallis, the British commander-in-chuff in the South. After Greene crossed the Can, Cornwallis gave up a chase that was bringing him no result, and fell back to Hillsboro, then the capital of North Carolina. Greene was joined by large numbers of militia, until his army was 4400 strong, but only one of his little regiments was of seasoned troops, and the militia organizations were an uncertain reliance. The force under Cornwallis was only half as numerous, yet his men were veterans, well-equipped and well officered. Greene recrossed the Dan and took position at Guilford, where he was attacked by the British, March 15th. Cornwallis held the battleground, but one-third of his army was put out of action by the American rifles. He could neither follow up his nominal advantage nor remain in North Carolina. He made a rapid retreat to Wilmington, pursued a part of the way by Greene, who then advance into South Carolina. Cornwallis dared not follow his antagonist, and led his shattered army to Virginia. In four months Greene nearly freed South Carolina and Georgia front he enemy, except as tot he seaports of Charleston and Savannah.

Rockbridge men under Captain James Gilmore helped to win the brilliant victory at the Cowpens. Their time had nearly expired, and they were used to escort the captured redcoats to their prison camp. In this fight Ensign John McCorkle was wounded in the wrist and died of lockjaw. But Capt. Gilmore seemed also to have been present at Guilford, where soldiers form Rockbridge were much more numerously represented. In this battle, Major Alexander Stuart was wounded and captured, and Captains John Tate and Andrew Wallace were killed. Among the other officers were Major Samuel McDowell, Captain James Bratton, and Captain James Buchanan. Tate's company was composed almost wholly of Students from Liberty Hall. They acquitted themselves so well as to extort a compliment from Cornwallis. After the action he asked particularly about "the rebels who took position in an orchard and fought so furiously." Samuel Houston, then a youth of nineteen, kept a diary while his company was on its tour. James Waddell, the preacher who was so noted for his eloquence, addressed the command at Steele's Tavern, the place of rendezvous. The company left Lexington January 26th, joined Greene's army five days before the battle of Guilford, and got home March 23rd. Houston fired nineteen rounds during the engagement. The men had orders to take trees and several would get behind the same tree. The redcoats were repulsed again and again. At Guilford, as at the Cowpens, the conduct of the Virginia militia was exceptionally good. Greene said if he could have known hoe well they would act, he could have won a campaign.

meanwhile the traitor Arnold had landed 1600 men at Westover on the James. Two days later, January 5th, he burned Richmond. Finding his flank threatened from the direction of Petersburg, he retreated to Portsmouth, where he was closely watched by a small army under Steuben and Muhlenburg. Colonel Bowyer had a regiment under Muhlenburg, the clergyman-general. The company of Captain Andrew Moore marched from its rendezvous at Red House, January 10, 1781.

Virginia had been stripped of her trained soldiers, and Washington sent Lafayette to take command. The young Frenchman arrived in March with 1200 light infantry. To offset this help, General Phillips left New York with two regiments and occupied Manchester, April 30th. The British much outnumbered the Americans, but were not aggressive. Phillips died of fever at petersburg, and Arnold was again in chief command. When Cornwallis arrived he brought the British army to a strength of 7000 men. Having no use for Arnold, he sent him away. The odds against the Americans were now serious. Late in May, Cornwallis moved from Richmond to gain the rear of Lafayette's army. He wrote that the boy could not escape him. yet the boy did escape him, although he was pursued nearly to the Rapidan. Cornwallis then sent out marauding expeditions under Tarleton and Simcoe, while his main army moved upon Orange. Lafayette, reenforced by 800 veterans under General Wayne, recrossed the Rapidan. Cornwallis thought he would cut him off, but Lafayette opened an old road and marched by night to Mechum's River, where, with his back tot he Blue Ridge, he made a stand to protect his stores. The British leader did not try to force a decision, and fell back to the Peninsula below Richmond. Tarleton had burned Charlottesville, then a very small place, and the Assembly fled from it to Staunton, where it sat from June 7th to the 24th. Tarleton made a threat of coming over the Blue Ridge. The legislators fled from Staunton so precipitately as to take no measures to defend the place. But the militia assembled in force, their ranks swelled by old men as well as boys, and meant to give Tarleton a hot reception, in case he should attempt to force Rockfish Gap. But as Tarleton had only 250 men, his threat could have been no more than a bluff.

Lafayette, gradually reenforced by the Virginia militia to the number of 3,000, followed the British. Washington came down from the Hudson with 2,000 of his American troops and 5,000 Frenchmen. The sequel was familiar to every reader of American history. Previous to the siege of Yorktown, the two small battles of Hot Water and Green Spring, fought near Williamsburg, were the only engagements in the Virginia campaign that rose above the dignity of mere skirmishes. During his almost unobstructed march, Cornwallis inflicted a loss of $10-million in looting and burning, and the kidnapping of slaves.

Not only did the Valley men have to contend with the British east of the Blue Ridge and the Indians west of the Alleghany, but in the spring of 1781 they had also to watch the Tories in Montgomery. The latter were threatening to seize the lead mines near Fort Chiswell, and then join Cornwallis, when, as was expected, he would follow Greene into Virginia.

Among the men from Rockbridge county who turned out to fight the invader in 1781 were companies under Colonel John Bowyer and cations Andrew Moore, Samuel Wallace, John Cunningham, William Moore, David Gray, James Buchanan, and Charles Campbell. Captain William Moore helped to guard the prisoners during their march from Yorktown to the detention camp at Winchester.

There was little active disloyalty in Rockbridge. Archibald Alexander says there were few Tories, and he intimates that these found it advisable to seek a change of climate. One was John Lyon, who had been a servant to Alexander's father. He deserted tot he British, and was one of the miscreants who bayoneted the hacked and helpless men not he field of Waxhaw, although he still had enough humanity to spare the life of John Reardon. Lyon was killed at Guilford. Tory Hollow, near the head of Purgatory Creek, derives its name front he Tories who fled into it and were not molested. Doubtless they were wise enough not to make their plight needlessly severe. There was another Tory Hollow between collier's and Kerr's creeks,a nd it may take its name from the Tory branch of the Cunningham family. Robert Cunningham, a son of John of Kerr's Creek, became a brigadier-general in the British army in South Carolina. His conduct made him so odious that his estate was confiscated, and although he petitioned to be granted to return, he had to spend the rest of his life under the Union Jack. He was granted an annuity by the British government. His brother Patrick, although a colonel in the British army, was not exiled from South Carolina.

There was discontent, and there was sometimes a disinclination to perform military service. It was related to Edward Graham that he found the militia assembled near Mount Pleasant about 1778, quite unwilling to volunteer instead of being drafted. Special inducements were offered, but without visible result. Graham addressed the meant o induce them to supply the quota with volunteers. Captain John Lyle and a few others stepped forward, and marched and counter-marched before the militia, but without effect. Graham then joined the volunteer squad himself, and was followed by enough of the unwilling crowd to make out the number desired. Like some other persons,this minister did not thick well of the headlong flight of the legislators from Staunton. He was on his way home from attending a presbytery, and at once set about raising a force of respectable size, acting as its leader.

The most serous disaffection seemed to have taken place in May, 1781. It grew out of an Act of Assembly of October, 1780, whereby the counties were to be laid off into districts for the purpose of procuring a quota from each to serve in the Continental line for eighteen months. A petition was sent to the capital from Rockbridge, representing that an absence from home for that length of time meant ruin to the family of the soldier. districts had been laid off in this county, and in two or three instances the quota had been procured. Jefferson, then governor of the state, pursued a vacillating course and hesitated to enface the conscription law. Then he wrote a letter taking off the suspension, but by that time the day appointed for the draft had gone by. A date was set for another laying off of the districts. A hundred people gathered at the county seat, May 9th. Hearing that the Augusta people had prevented such action in their county, and seeing Colonel Bowyer getting lists form the captains, a crowd went into the courtroom and carried out the tables. The men said they would serve three months at a time in the militia and make up the eighteen months in that manner, but would not be drafted as regulars for the term mentioned in the law. After tearing up the papers the crowd dispersed.

Virginia was prosperous when the Revolution broke out, but there was much distress during the war. Trade with England came necessarily to an end, and was carried on with France at great risk. Specie was scarce, and there was a tendency to keep it hidden. The currency issued but he Continental Congress to pay its war claims rested on a very insecure basis, and Henry Ruffner related that it operated as a tax because of its rapid depreciation. In March, 1780, the ratio of paper to specie was forty to one, and in May, 1781, it was 500 to one. Taxes were high and hard to meet, and the collecting of them was an unpleasant official duty. Almost everything was taxed, even the windows in a house. A petition of 1779 complains not only of the high assessment, but says that a still greater grievance was the separate taxing of houses, orchards, and fencing, these items aggregating more than the land itself. It was made legal for taxes to be paid in certain kinds of farm produce. This form was called the specific tax, and it required storehouses for the produce livid upon.

Samuel Lyle and John Wilson, the commissioners, were allowed ten percent for their services. A petition of 1784 said there was little or no hard money, and that the number of horses and cattle had been much reduced during the war. The only merchantable staple was hemp, and this had fallen in price very much.

Under the Federal pension law of 1832, the applicant was required to make his declaration before the county court, and his reminiscences were often of interest and value. The declarations below were by men who were living in Rockbridge in the year indicated. A less abbreviated account (more service to genealogists) may be found in McAllister's Data on the Virginia Militia in the Revolutionary War.

Federal pension Law of 1832 (Applicants)

- Ailstock, Absalom: born a free mulatto about 1795. Marched from Luisa about December 1, 1780, it being rumored that the British were going to land on the Virginia coast, and was out four weeks. About April 1, 1781, joined the Second Regiment under Colonel Richardson. The ruins of the tobacco warehouses in Manchester could be seen from the Richmond side. The brigade was stationed awhile at Malvern Hills. The enemy were in the habit of coming this far up the James in boats, each with a gun at either end, the purpose being plunder. Two such boats and seventeen men were taken by the regiment. During the siege of Yorktown the applicant dug entrenchment's for batteries and made sand baskets.

- Cunningham, John: Born in Pennsylvania in 1756. Served in that state in 1776, 1777, and 1781.

- Davidson, John: born in Rockbridge, 1757. he was willing to go out in the spring of 1778, being then unmarried, but was induced by his mother to hire a substitute. In the summer of that year, as a drafted man, he served in Greenbrier. Under Captain William Lyle he drove packhorses loaded with four and bacon to the troops on the frontier. In January, 1781, he marched from Red House, his company condors being Captain Andrew Moore, Lieutenant John McClung, and Ensign James McDowell. At Great Bridge, near Norfolk, two twelve pounder howitzers and about twelve prisoners are captured. There was another kirmess near Gum Bridge, near the Dismal Swamp. He went out again, August 7, 1781, under attain David Gray, who tried to induce him to be orderly sergeant. At Jamestown the militia were ferried across the James by the French, who were 5,500 strong on the north side.

- East, James: born in Goochland, 1753. In 1779 he was guarding Hessian prisoners at Charlottesville. Left Fluvanna county, 1792.

- Fix, Philip: born near Reading, Pennsylvania, about 1754. Was living in Loudoun county, 1777, and served that year in his native state.

- Harrison, James: born in Culpeper, 1755. In the fall of 1777 he served under Captain John Paxton, marching to Point Pleasant by way of Fort Donally. He witnessed the death of Cornstalk, Red Hawk, petal, and Ellinipsico. He reached home shortly before Christmas. In 1781 he was engaged six months in Amherst, his duty being to patrol the county twice a week to thwart any effort by the Tories to stir up disaffection among the negroes.

- Hickman, Adam: born in Germany, 1762, and came to America five years later. Served under Captain James Hall in 1780. that company and Captain Gray's marched about October 1, and was absent three months around Richmond and Petersburg. He went out again in May, 1781, and the Appomattox at Petersburg was crossed on a flatboat, the bridge having been burned by the enemy. He was in the battle of Hot Water, June 28th.

- Hight, George: born in King and Queen, 1755. Was in Christian's expedition against the Cherokees. In August, 1777, he enlisted in Rockbridge for the war, serving in colonel George Baylor's Light Dragoons. In October, he joined the regiment at Fredericksburg, and the following winter was at Valley Forge. The troop to which he belonged was employed in preventing the people of that region from furnishing supplies to the enemy, and in watching the movements of the latter. He was in the battle of Monmouth. Next September, at a time when the regiment was asleep in barns on the Hudson, it was surprised by General Grey, and no quarter was given except to the members of his own troop. He and another man escaped by getting in among the enemy. In the spring of 1779 the regiment was recruited,and Colonel William Washington took command. It was again employed, this time in New jersey, in watching the enemy and preventing trading with him. Near the close of 1780 the regiment marched to Charleston, South Carolina. Shortly after his arrival in March, Washington defeated Tarleton, taking sixteen prisoners, but awhile later was himself defeated t Monk's Corner. The horses were saddled and bridled, but there was no time to mount them. applicant was taken prisoner and was exchanged at Jamestown, in August, 1781.

- Hinkle, Henry: born in Pennsylvania, 1750. Served three tours in the militia of Frederick county, 1789-1781.

- Kelso, James: born on Walker's Creek, 1761. Drafted, January, 1781, into Captain James Buchanan's company of Colonel Bowyer's regiment, and was in skirmishes near Portsmouth. When Tarleton made his raid on Charlottesville, he volunteered and served one month. In September he was at the siege of Yorktown, under Captain Charles Campbell, and after that event he was detailed to guard the prisoners to winchester.

- Mason, John: born in Pennsylvania, 1740. Was in the battle of Brandywine, serving in a company form Berkeley. In 1781 he was in the battle of Guilford as a member of John Tate's company.

- mcLane, John: born in Ulster, 1757.. In 1778 served in Greenbrier under Captain David Gray. In january, 1781, he went out on a tour of three months under Captain Andrew Moore. It took about fifteen days to get home from Norfolk.

- McKee, James: born in Pennsylvania, 1752, died in Rockbridge, 1832. Declaration by Nancy, the widow. John T., a son. Total service, seventeen months, twenty-nine days. His first service was three months with Christian in the Cherokee expedition. The second was when he marched under Captain Charles Campbell and Lieutenant Samuel Davidson to Point Pleasant in the fall of 1777. The third was a tour of three months in Greenbrier, jet after the Shawnees attacked Donally's fort. The fourth was as an ensign in the spring of 1781, at which time he marched to Portsmouth. In the summer of the same year he served on the Peninsula. In the fall he served his last tour, and was at the siege of Yorktown.

- Miller, William: born in Pennsylvania, 1757, and came to Rockbridge about 1770. October 9, 1780, he went out under Captain James Gilmore, Lieutenant John Caruthers, and Ensign John McCorkle, and was in the battle of the Cowpens. For four weeks he was guarding Garrison's Ferry on the Catawba.

- Sheperdson, David: born in Louisa, 1763, came to Rockbridge, 1815. In june, 1780, he marched to join the army of Gates, and at Deep River himself and comrades nearly perished, having nothing but green crabapples to eat. A detail of 200 men was sent out to thresh some grain. Was in the battle near Camden, August 16th. After the retreat to Hillsboro, provisions became so scarce that the captain advised the men to go home and get provisions and clothing, their clothing having been lost at Camden. They did so and returned, were advised to go home again, and on their second return were honorably acquitted by a court matial. Next year he served six months on the Peninsula, and was present at the surrender of Cornwallis.

- Vines, Thomas: born in Amherst, 1756. Served at Charlottesville and Winchester, guarding prisoners. Was int he battles of Hot Water and Green Spring and at the siege of Yorktown.

- Wiley, Andrew: born in Rockbridge, 1756. Absent forty-two days in 17777, driving cattle tot he mouth of Elk on the Kanawha. In 1778-79, he served twelve months in the Continental line under General Morgan. In the fall of 1780, he was a substitute in Captain James Hall's company. This company and those of Campbell and Gray joined Greene's army at Guilford as a member of a Botetourt company. The Carolina men, who formed the first line, ran at the outset. The riflemen to which applicant belonged formed the covering party at the left, and when the Carolina men fled, the British came down on a ridge between this party and the command of Colonel Campbell. The enemy were swept off by the Virginia riflemen, but formed again and again, and compelled the party to ground their arms. Captain Tilford was killed. Andrew Wiley was one of the Virginians who marched against the "Whiskey Boys," in 1794,

| © . Linda Mcgill Wagner - began © 1999 Contact Me | |